Inevitability, that alluring progeny of passivity, is a card often played from the bottom of history’s deck through a sleight of hand. A deft example of such a play has appeared recently in Alix Harrow’s New York Times op-ed from the future, Books May Be Dead in 2039, but Stories Live On.

Inevitability, that alluring progeny of passivity, is a card often played from the bottom of history’s deck through a sleight of hand. A deft example of such a play has appeared recently in Alix Harrow’s New York Times op-ed from the future, Books May Be Dead in 2039, but Stories Live On.

Given that Harrow’s absorbing interest in the supple adaptability and power of stories is everywhere on display in her excellent debut novel, The Ten Thousand Doors of January, it is apropos that she employs these themes from her book in Books May Be Dead in 2039, but Stories Live On. Another given is that Harrow loves books, and her essay’s depiction of a world that has just barely moved across the threshold of their demise is imbued with a disarming affection for the deceased.

The essay argues, however, that the proper, enlightened object of our shared affection resides in an attachment to its vital force, storytelling, a force which survives the evolutionary adaptations of its physical form. To adhere to the physical form itself is to become irrelevant, a lover of facile, discarded antiques and would be artifacts, bereft of all but the memory of past vitality. According to our essayist from the future, as the vehicle for animating stories changed, from books to virtual reality, engaged readers followed the stories blithely. Nostalgia for their obsolete physical shells, books, became the province of hipsters or those otherwise bibliographically infirm due to age or temperament. Indeed, it is these elegy seeking persons who, in 2039, have made “indie bookshop” a bestselling candle scent.

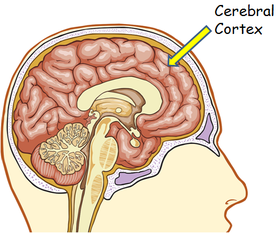

Harrow’s essay has a good deal of fun with tech, projecting an evolution in virtual reality, into a storytelling apparatus called the Verse, which can “impart any combination of sensory experiences directly into your cortex.” The proprietary intentions of Verse’s original creator, Amazon, were broken by the hacking of the Verse “to the collective chagrin of Amazon’s stockholders, it was destined to end proprietary storytelling.” Indeed the whole enterprise became a kind of globally rampant 3D printed physical freeware.

Harrow’s essay has a good deal of fun with tech, projecting an evolution in virtual reality, into a storytelling apparatus called the Verse, which can “impart any combination of sensory experiences directly into your cortex.” The proprietary intentions of Verse’s original creator, Amazon, were broken by the hacking of the Verse “to the collective chagrin of Amazon’s stockholders, it was destined to end proprietary storytelling.” Indeed the whole enterprise became a kind of globally rampant 3D printed physical freeware.

The argument that attachment to form is an historical illusion has a basis, but is also itself a kind of deception. It is true of course that a segment of every generation believes that the last one was more moral, that teenagers are running wild, and that some new technological innovation is ruining something precious. These dubious convictions can be found continually across time. As these sentiments cannot possibly be perpetually true, they clearly say more about intrinsic dissatisfaction with the human condition than anything else. Consider the topic at hand, the demise of the book.

Harrow’s op-ed, set in 2039, marks the end of the book 600 years after the Gutenberg Bible marked the advent of the printing press. We do well to bear in mind that scholars of the time, such as Robert Burton, saw the advent of the printing press as a menace to readers. Here he is opining that in The Anatomy of Melancholy.

“What a catalogue of new books all this year, all this age (I say), have our Frankfort Marts, our domestic Marts brought out? Twice a year, Proferunt se nova ingenia et ostentant, we stretch our wits out, and set them to sale, magno conatu nihil agimus. So that which Gesner much desires, if a speedy reformation be not had, by some prince’s edicts and grave supervisors, to restrain this liberty, it will run on in infinitum. Quis tam avidus librorum helluo, who can read them? As already, we shall have a vast chaos and confusion of books, we are oppressed with them, our eyes ache with reading, our fingers with turning.”

No prince’s edict appeared and the modern age of printing thus continued unabated at least until the year 2039. Humorous as Burton’s sense of catastrophe is, he was nonetheless expressing a change whose merits it is hard for us to judge. The ethos of reading every book published, due to the small scale of publications, presumably had a character that had real worth. This does not mean that change is bad, but rather that a sense of loss is not necessarily fatuous.

At the risk of falling into the very trap that I have described I declare that I think the transition to the virtual reality form of storytelling Harrow describes represents a more substantive loss by far than that change initiated by Gutenberg.

The core of Harrow’s perspective is found in her declaration that “Books may be dead, but the stories themselves — those unruly creatures we trapped in paper and pixels, the narratives that delight and dismay and define us — are still very much alive …. Why read comic books when you can live them, leaping tall buildings in single bounds, doing whatever spiders can? Why sit in a movie theater, surrounded by the stale salt smell of popcorn, when you can ride the fury road yourself, shiny and chrome?”

The core of Harrow’s perspective is found in her declaration that “Books may be dead, but the stories themselves — those unruly creatures we trapped in paper and pixels, the narratives that delight and dismay and define us — are still very much alive …. Why read comic books when you can live them, leaping tall buildings in single bounds, doing whatever spiders can? Why sit in a movie theater, surrounded by the stale salt smell of popcorn, when you can ride the fury road yourself, shiny and chrome?”

Harrow has a lot of fun here but the core of this issue, the actual nature of change between Verse and printed word, is glossed over by all these sleight of hand flourishes set against a background of inevitability reinforced by the fait accompli perspective of a future narrative.

The permeability of virtually transmitted experience, one in which all our senses are commandeered, should be set against the backdrop of a simple equation. The more permeable and reactive the medium, the less imaginative effort is called upon by the end user. The fixed nature of printed books, the “unruly creatures we trap in paper,” calls upon the reader to create their experience in the theater of the individual mind. The more the story is transmitted in a controlled responsive and dynamic sensory environment, the less the experience is personally dynamic.

Harrow’s argument regarding the benign dethronement of proprietary filters by crowd sourcing is also dubious. She cites the conversion of Independent bookstores to antique shops and the recent closing of the last of the big five publishers and the last Barnes and Noble store. Could proprietary filters die? Sure. Would the result be a happy evolution in the storytelling continuum, leaving only a trail of facile nostalgia in its wake? That would be no. Her assertion that stories will be just fine rings hollow to anyone who curates and deals with the unpublished and the self published. The death of professional filters would be profoundly substantive and charnel in character.

Is this really the future? One way to be certain of making it so is to be passive in the face of the threatened displacement of the physical book. Will the vital force of books live on after the end of proprietary storytelling in 2039 as Harrow suggests? I suppose that will depend on which virtual reality episodes set in the past, those adaptable interactive stories we once quaintly thought of as history, one subscribes to.

On the Book in 2039

Kenny Brechner - December 5, 2019

Leave a reply