Several years ago, I saw a mesmerizing documentary on PBS about an eight-month collaboration (from November 1998 to June 1999) between Maurice Sendak, Arthur (Hey, Al) Yorinks, and the dance troupe Pilobolus. The dance was inspired—at least on Sendak’s part—by the true story of a fake "work camp," Terezín, built by Nazis to fool the international world into thinking that interned Jews were happy, healthy, productive, even artistically fulfilled, citizens. (More on that in a moment.)

Several years ago, I saw a mesmerizing documentary on PBS about an eight-month collaboration (from November 1998 to June 1999) between Maurice Sendak, Arthur (Hey, Al) Yorinks, and the dance troupe Pilobolus. The dance was inspired—at least on Sendak’s part—by the true story of a fake "work camp," Terezín, built by Nazis to fool the international world into thinking that interned Jews were happy, healthy, productive, even artistically fulfilled, citizens. (More on that in a moment.)

I loved this film so much I wanted to see it again right away, but I hadn’t recorded it, and this was back in the early 2000s when semi-obscure documentaries were not widely available. "Last Dance" became my "lost chord" of films, the first title I looked for when I joined Netflix years ago, the movie I Googled whenever I had a hankering to revisit the creative genius and collisions of two brilliant, obsessive artistic forces. Back then, I was out of luck. But now—now, you lucky newcomers among us!—the film is back. Ten years later, you can see this film, evocative as the day it was released, on Netflix, either through the mail on DVD or right this minute (if you’re a Netflix member) via live streaming on your computer.

"Last Dance," directed by PBS filmmaker Mirra Bank, is as much about the head-butting and breakthroughs inherent in collaborative work as it is about the resulting performance piece. Maurice Sendak, consummate storyteller and then-co-director with Yorinks of The Night Kitchen Radio Theater, was accustomed to using art, words, actors, and voices to bring stories to life. Pilobolus, on the other hand, was accustomed to an almost opposite process: dancers and choreographers first create interesting movements and body shapes, and then find the story that grows out of them.

The push-and-pull is fascinating to watch, especially because the work evolves despite (and perhaps because of) the artistic conflict. At one point, Pilobolus’s Jonathan Wolken casually mentions that he is not wedded even to the theme of the Holocaust—which, as anyone familiar with Maurice Sendak’s work will anticipate, is nearly a breaking point for Sendak and Yorinks. Fortunately, a story both consistent with and different from their original vision slowly blooms as the dancers begin to use movement to create characters. One dancer in particular, Otis Cook (pictured at right in a screen capture from "Last Dance"), is stunning, almost other-worldly, in his development of a hunched and twisted, yet sinuous and powerful, dark presence in the vignette.

The push-and-pull is fascinating to watch, especially because the work evolves despite (and perhaps because of) the artistic conflict. At one point, Pilobolus’s Jonathan Wolken casually mentions that he is not wedded even to the theme of the Holocaust—which, as anyone familiar with Maurice Sendak’s work will anticipate, is nearly a breaking point for Sendak and Yorinks. Fortunately, a story both consistent with and different from their original vision slowly blooms as the dancers begin to use movement to create characters. One dancer in particular, Otis Cook (pictured at right in a screen capture from "Last Dance"), is stunning, almost other-worldly, in his development of a hunched and twisted, yet sinuous and powerful, dark presence in the vignette.

The dance, eventually titled "A Selection," premiéred in 1999, to mixed reviews. You can judge it for yourself; much of the performance is included at the end of "Last Dance."

Sendak a lso collaborated on another project with the same theme, this time working with Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner. Kushner wrote the libretto and text and Sendak created the sets (example from the Berkeley Repertory Theatre performance is at left) for "Brundibar," based on a children’s opera composed in 1938 by Hans Krása, a Czech Jewish musician whose work was performed at Terezín before his final, fatal transport to Auschwitz.

lso collaborated on another project with the same theme, this time working with Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner. Kushner wrote the libretto and text and Sendak created the sets (example from the Berkeley Repertory Theatre performance is at left) for "Brundibar," based on a children’s opera composed in 1938 by Hans Krása, a Czech Jewish musician whose work was performed at Terezín before his final, fatal transport to Auschwitz.

Krása had actually composed the score for his opera as a free man and rehearsed it with boys in a Jewish orphanage in Prague before political turmoil interrupted the project. The orphans eventually performed it in 1941, but without Krása; by then, he had been deported to Terezín. When many of the children from the orphanage were also transported to Terezín, Krása used smuggled fragments of the musical score to reconstruct and adapt his opera for the camp, where it became part of a Nazi propoganda film. (The black-and-white photo above, owned by the Jewish Museum in Prague and found on the Terezín Memorial website, shows the children’s choir depicted in the film, "Theresienstadt.")

Brundibar means "bumblebee" in colloquial Czech, and Krása’s opera told the story of two children who manage to outwit a greedy, malicious bully with the help of a few wise animals and a multitude of fellow schoolchildren. The Nazi camp leaders didn’t seem to recognize the subversive irony of this production with a message about strength in numbers and good triumphing over evil, but the children (audience and performers alike) enjoyed the rare measure of hope and strength and solidarity the opera brought, even if briefly. The opera was performed 55 times in the camp with a cast that continually changed as children were shipped out to their various fates at Auschwitz and beyond.

One survivor, Ela Weissberger, played the cat in the production; her memories of that time are recounted in The Cat with the Yellow Star: Coming of Age in Terezín (co-written with Susan Goldman Rubin; Holiday House). Another survivor, Zuzana Justman, directed an award-winning documentary about the experience, called "Voices of the Children" (which, sadly, doesn’t seem to be available for viewing). And there’s an extraordinary book, I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children’s Drawings and Poems from Terezin Concentration Camp, 1942-1944 (Schocken), that was the basis for a play. (Odd coincidence: 27 years ago, my high-school friend Angela Price directed me in this play; I played Irena Synkova, a Terezín teacher who defied the Nazis by giving the children the gift of artistic expression, with contraband paper and paints, and songs. Yet another example of the way our lives circle around and around and connect up to themselves again, isn’t it?)

One survivor, Ela Weissberger, played the cat in the production; her memories of that time are recounted in The Cat with the Yellow Star: Coming of Age in Terezín (co-written with Susan Goldman Rubin; Holiday House). Another survivor, Zuzana Justman, directed an award-winning documentary about the experience, called "Voices of the Children" (which, sadly, doesn’t seem to be available for viewing). And there’s an extraordinary book, I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children’s Drawings and Poems from Terezin Concentration Camp, 1942-1944 (Schocken), that was the basis for a play. (Odd coincidence: 27 years ago, my high-school friend Angela Price directed me in this play; I played Irena Synkova, a Terezín teacher who defied the Nazis by giving the children the gift of artistic expression, with contraband paper and paints, and songs. Yet another example of the way our lives circle around and around and connect up to themselves again, isn’t it?)

Brundibar in book form became Sendak’s third and final iteration of this  Holocaust story, although where Maurice Sendak is concerned, there is never an end to the theme of good and evil wrestling against a backdrop of political corruption, or even wrestling within ourselves.

Holocaust story, although where Maurice Sendak is concerned, there is never an end to the theme of good and evil wrestling against a backdrop of political corruption, or even wrestling within ourselves.

In a 2004 interview with Bill Moyers, he said,

"I was watching a channel on television. And they had Christa Ludwig who was a great opera singer…. And then, she had a surprising interview at the end of the concert where… [the interviewer] said, ‘But, why do you like Schubert? You always sing Schubert.’ And he sort of faintly condemned Schubert. ‘I mean, he’s so simple. He’s just Viennese waltzes.’ And she smiled. And she said, ‘Schubert is so big, so delicate, but what he did was pick a form that looked so humble and quiet so that he could crawl into that form and explode emotionally, find every way of expressing every emotion in this miniature form.’ And I got very excited. And I wondered, is it possible that’s why I do children’s books? I picked a modest form which was very modest back in the ’50s and ’40s. I mean, children’s books were the bottom end of the totem pole. We didn’t even get invited to grownup book parties at Harper’s…. And you were suspect the minute you were at a party, "What do you do?" "I do books with children." "Ah, I’m sure my wife would like to talk to you." It was always that way. It was always. And then when we succeeded, that’s when they dumped the women. Because once there’s money, the guys can come down and screw the whole thing up which is what they did. They ruined the whole business. I remember those days. And they were absolutely so beautiful. But, my thought was… that’s what I did. I didn’t have much confidence in myself… never. And so, I hid inside, like Christa was saying, this modest form called the children’s book and expressed myself entirely."

And this is where I think Sendak and Pilobolus finally found their common ground: in a form—the human body or a picture book—so seemingly humble and quiet, but so ready to explode emotionally. As Sendak says in "Last Dance": "You make the whole thing up anyway. You sit there, they sit there, we’re all making it up…. So if you’re making it up, make it up good."

If you want to know more about Terezín and Brundibar, or children and the Holocaust, PBS has a great website here. And the transcript of the interview with Bill Moyers is here. And just for Sendakian fun, if you haven’t seen it yet, check out the trailer for the upcoming live-action movie of Where the Wild Things Are. I’m cautiously optimistic that the book’s integrity might not be completely shredded by the Hollywood machine.

UPDATE: In following up on Pamela Ross’s comment below, I discovered that the Rosenbach Museum did make a DVD about the now-closed Sendak exhibit that sounds well worth looking at:

![IMG_4366[1].JPG](http://www.rosenbach.org/shopsite/media/IMG_4366%5B1%5D.JPG)

$20.00

This DVD is a a companion to the Sendak on Sendak Exhibit at the Rosenbach, 2008-2009. It includes interviews with Sendak from the exhibit, as well as additional stories, anecdotes, and memories from the artist himself, not included in the exhibit.

[Add to Cart] [View Cart]

How about you? Any thoughts on Sendak? "Last Dance?" Brundibar? Wild Things?

box, but at least they’re out of the way.

box, but at least they’re out of the way. Following a theme that’s best summed up as "every parent’s worst nightmare," the first half of this episode features interviews with journalist/mother and now author Debra Gwartney and her two daughters, all of whom recount what happened before and after the girls (then ages 13 and 15) ran away from home. Their story is frightening, fascinating and heartbreaking in ways you might not expect.

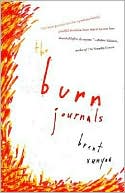

Following a theme that’s best summed up as "every parent’s worst nightmare," the first half of this episode features interviews with journalist/mother and now author Debra Gwartney and her two daughters, all of whom recount what happened before and after the girls (then ages 13 and 15) ran away from home. Their story is frightening, fascinating and heartbreaking in ways you might not expect.  As if the first isn’t moving enough, the second half of "Didn’t Ask to Be Born" features Brent Runyon reading an excerpt from his harrowing and beautiful memoir

As if the first isn’t moving enough, the second half of "Didn’t Ask to Be Born" features Brent Runyon reading an excerpt from his harrowing and beautiful memoir

Dr. Seuss’s

Dr. Seuss’s  Some of our favorites are handsome editions of classic books, fit to grace a scholar’s lifetime bookshelf. The Riverside Shakespeare is fantastic for literature lovers with every play and sonnet in the canon, and remains a favorite from my own high school graduation. Mine was a boxed set with two volumes, and the tall, slim red-cloth books still have their (slightly worn now) gilt lettering that evokes the magic of the language inside. This is my favorite book in the world, my desert-island necessity, and a good-luck charm of sorts: I pressed Vermont fall leaves in it in 1990, years before I decided to move here. (I like to think the book knew before I did.) Though The Riverside Shakespeare no longer comes in two volumes, it’s still a great-looking book with endless worlds inside.

Some of our favorites are handsome editions of classic books, fit to grace a scholar’s lifetime bookshelf. The Riverside Shakespeare is fantastic for literature lovers with every play and sonnet in the canon, and remains a favorite from my own high school graduation. Mine was a boxed set with two volumes, and the tall, slim red-cloth books still have their (slightly worn now) gilt lettering that evokes the magic of the language inside. This is my favorite book in the world, my desert-island necessity, and a good-luck charm of sorts: I pressed Vermont fall leaves in it in 1990, years before I decided to move here. (I like to think the book knew before I did.) Though The Riverside Shakespeare no longer comes in two volumes, it’s still a great-looking book with endless worlds inside.

Another classic we sell oodles of for graduates is Homer’s

Another classic we sell oodles of for graduates is Homer’s  For sheer aesthetic pleasure, we also love love LOVE Pablo Neruda’s

For sheer aesthetic pleasure, we also love love LOVE Pablo Neruda’s

For the energetic, service-oriented graduate who loves travel, hands-on work, and cultural exchange, Moritz Thomsen’s

For the energetic, service-oriented graduate who loves travel, hands-on work, and cultural exchange, Moritz Thomsen’s

wn women are marching straight up the counter and asking for “that book.” Admittedly, they are a little sheepish about buying the Twilight books by Stephenie Meyer. But I don’t think it’s because it’s written for young adults. It’s because they love it so much. They can’t wait to read more about Edward and Jacob, who they are more than happy to talk about, at great length with other women in the store. One thing I particularly enjoy about these Twilight women is they tend to buy the whole series at one time. Sure, they tell daughters to wait, space out their purchases, save some money, and maybe even borrow from a friend. There’s none of that with the adults. No borrowing, no waiting for the book at the library, no, they need it, they need it now and they’re going to pay for their immediate gratification. And I love them for it.

wn women are marching straight up the counter and asking for “that book.” Admittedly, they are a little sheepish about buying the Twilight books by Stephenie Meyer. But I don’t think it’s because it’s written for young adults. It’s because they love it so much. They can’t wait to read more about Edward and Jacob, who they are more than happy to talk about, at great length with other women in the store. One thing I particularly enjoy about these Twilight women is they tend to buy the whole series at one time. Sure, they tell daughters to wait, space out their purchases, save some money, and maybe even borrow from a friend. There’s none of that with the adults. No borrowing, no waiting for the book at the library, no, they need it, they need it now and they’re going to pay for their immediate gratification. And I love them for it.

necdote I must share. One of my favorite customers comes in every Monday to get her books for the week. Jill is the most vital, active, and vibrant 78-year-old I’ve ever met. She is a well-rounded reader with eclectic tastes. Last week she was struggling to choose a book when she went to the young adult section. There she saw I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. She had read the book when she was 19 and remembered loving it. Well, she took it with her last weekend and was still beaming when she came in Monday to tell me about reading it again. She sat in the sun in an Adirondack chair with Beethoven on in the background and a glass of Merlot nearby. She read the book she first loved 60 years ago. “It was just marvelous. Marvelous.”

necdote I must share. One of my favorite customers comes in every Monday to get her books for the week. Jill is the most vital, active, and vibrant 78-year-old I’ve ever met. She is a well-rounded reader with eclectic tastes. Last week she was struggling to choose a book when she went to the young adult section. There she saw I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. She had read the book when she was 19 and remembered loving it. Well, she took it with her last weekend and was still beaming when she came in Monday to tell me about reading it again. She sat in the sun in an Adirondack chair with Beethoven on in the background and a glass of Merlot nearby. She read the book she first loved 60 years ago. “It was just marvelous. Marvelous.” What happens when you click on a list? Let’s take

What happens when you click on a list? Let’s take

and options to either buy the book online or find a nearby bookstore.

and options to either buy the book online or find a nearby bookstore. (this is the BRILLIANT aspect of the iPhone, Big Brother concerns aside — it knows your location through GPS if you "allow" that function, so can find the closest indie source).

(this is the BRILLIANT aspect of the iPhone, Big Brother concerns aside — it knows your location through GPS if you "allow" that function, so can find the closest indie source). Wahoo!

Wahoo! "I have that. I have that one. Look, Mommy, Curious George." The familiar is comforting and surprising when it’s

"I have that. I have that one. Look, Mommy, Curious George." The familiar is comforting and surprising when it’s  so she could take a copy of Purplicious by Victoria Kahn off the top shelf of a display. The Tushy Book by Fran Manushkin had practically been mauled by kids under three. There’s something about a bottom that kids just seem to love. Another book that has kids — and it’s the boys again — begging to hear it read aloud, is Harriet Zieffert’s Mighty Max.

so she could take a copy of Purplicious by Victoria Kahn off the top shelf of a display. The Tushy Book by Fran Manushkin had practically been mauled by kids under three. There’s something about a bottom that kids just seem to love. Another book that has kids — and it’s the boys again — begging to hear it read aloud, is Harriet Zieffert’s Mighty Max.  Two books are easily spanning gender difference. Mouse Was Mad by Linda Urban has been an enormously popular toddler pick. I think the cover really draws kids in. There’s nothing like a non-threatening mouse who’s angry to get kids’ attention. This is a great book about emotions that I’ve heard read aloud just about every day. Duck! Rabbit! by Amy Krouse

Two books are easily spanning gender difference. Mouse Was Mad by Linda Urban has been an enormously popular toddler pick. I think the cover really draws kids in. There’s nothing like a non-threatening mouse who’s angry to get kids’ attention. This is a great book about emotions that I’ve heard read aloud just about every day. Duck! Rabbit! by Amy Krouse Rosenthal and Tom Lichtenheld is drawing kids in.

Rosenthal and Tom Lichtenheld is drawing kids in.