When your bookstore is in an urban center HONONI’s have happened and continue to happen all the time. They are important of course, but unexceptional and a matter of course. If your bookstore is in a rural town, however, a HONONI is an absolute singularity and a huge big deal. All right, slow down you say. What are HONONI’s, and did I coin that acronym just now? HONONI’s are Harbingers of Nonfiction of National Interest, historical events which spawn nationally released nonfiction books. Let’s face it, notable historical events happen all the time in cities. Take Boston, for example. A giant wave of molasses that immolates a whole neighborhood? Boston had one of those. The Boston Tea Party, even the title rubs it in. If you have a bookstore in an urban area, or even a suburban area, big nonfiction releases set locally happen regularly.

When your bookstore is in an urban center HONONI’s have happened and continue to happen all the time. They are important of course, but unexceptional and a matter of course. If your bookstore is in a rural town, however, a HONONI is an absolute singularity and a huge big deal. All right, slow down you say. What are HONONI’s, and did I coin that acronym just now? HONONI’s are Harbingers of Nonfiction of National Interest, historical events which spawn nationally released nonfiction books. Let’s face it, notable historical events happen all the time in cities. Take Boston, for example. A giant wave of molasses that immolates a whole neighborhood? Boston had one of those. The Boston Tea Party, even the title rubs it in. If you have a bookstore in an urban area, or even a suburban area, big nonfiction releases set locally happen regularly.

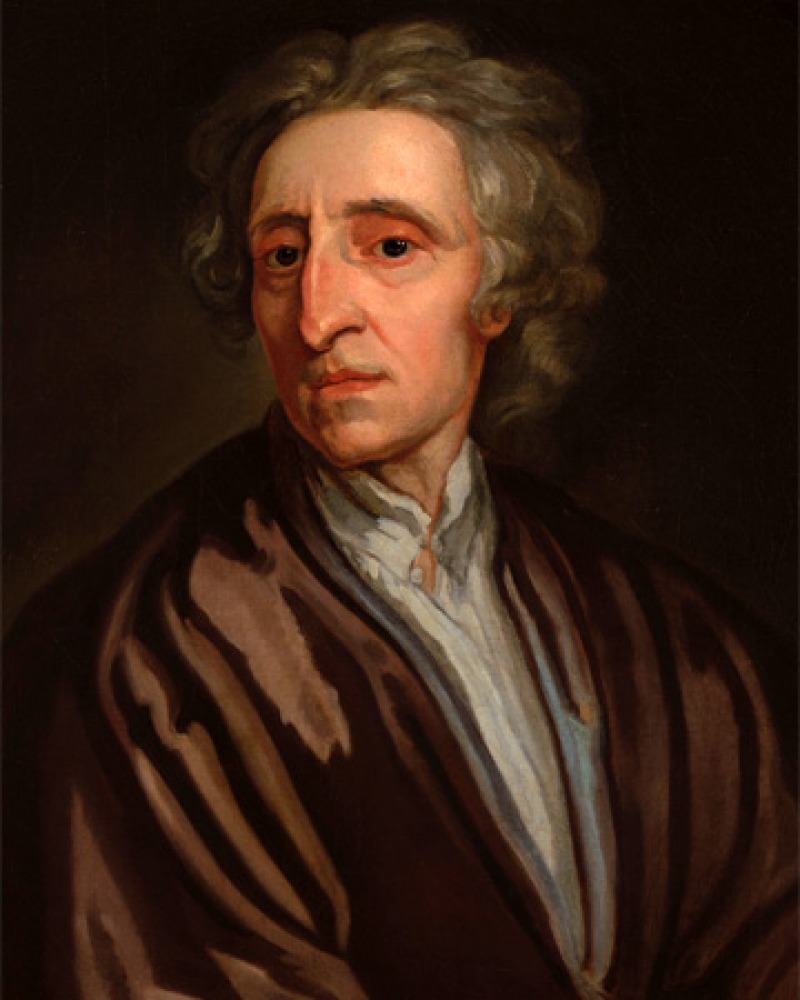

Author Michael Finkel. (credit: Christopher Anderson Magnum Photos)

One might think that if your bookstore is in rural Maine that HONONI’s pretty much never happen. If you’d asked me in 2014 I would have told you that was true. In the first 23 years of our store precisely no HONONI’s were published. When Meghan McCarthy’s fabulous Earmuffs for Everyone!: How Chester Greenwood Became Known as the Inventor of Earmuffs, was released it was a huge big deal, as reported here earlier. One might have thought we were done with HONONI’S for another quarter century, or perhaps forever. One would be wrong. Five months ago I was going through Random House’s Knopf spring list. I ran into The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit.

The Last True Hermit is Christopher Knight, who until he was arrested after living sought for but uncaptured in the central Maine Woods for 27 years, helping himself to food and supplies from seasonal cabins and a camp for disabled youth, was known as The North Pond Hermit. North Pond is right around the corner from where I live. This is a HONONI of seismic magnitude for DDG and central Maine in general, in part because it is of such enduring local interest, in part because Knight is a true outlier and his story is fascinating, and finally because this is a terrific book, based on rare personal access to Knight, and extremely well told.

Whether we never see another HONONI here or not, we are thrilled to be launching author Mike Finkel’s book tour next month. Obviously I had to catch up with him about the book.

(And yes, I did make up HONONI.)

Kenny: John Locke set his social contract in the background of government liberating individuals from the inequalities endemic to a state of nature. Did Christopher Knight turn that notion on its head?

Michael: I admit that I needed to spend some time re-reading Locke’s ideas before answering this. Locke, a 17th-century English philosopher, wrote widely on the subject of how much the state should or should not control the individual. Depending upon how you read Locke, one can state that Knight either rejected Locke’s ideas entirely, or was his greatest practitioner.

According to Locke, the State of Nature, the natural condition of mankind, is a state of perfect and complete liberty to conduct one’s life as one best sees fit, free from the interference of others. In this way, Knight seems a perfect match to Locke’s ideas.

According to Locke, the State of Nature, the natural condition of mankind, is a state of perfect and complete liberty to conduct one’s life as one best sees fit, free from the interference of others. In this way, Knight seems a perfect match to Locke’s ideas.And yet Locke also said that the Law of Nature, which in Locke’s view is the basis of all morality, commands that we not harm others with regards to their “life, health, liberty, or possessions.” Knight clearly harmed others by stealing, over and over, so in this way Knight’s actions seem a complete repudiation of Locke’s ideas.

I suppose the one thing you could say about Knight is that when it comes to Locke, as with so many other things, Knight is such an extreme outlier that no category really fits him well.

Kenny: The North Pond Hermit is certainly a largely sympathetic character in your book. Obviously, from an economic standpoint, there can’t be a world full of hermits living off other people’s goods. How much did the concept of Christopher’s genuine exceptionalism work into your understanding of and connection with him?

Michael: Knight’s exceptionalism won many people over, not just me. I really like what Sergeant Terry Hughes, the game warden who caught Knight, had to say. “Everything in my gut wanted to hate this guy,” said Hughes. “He stole food from a camp for disabled people. But I can’t hate him. You could work in law enforcement a hundred years and never come across anyone like this.”

Knight’s ability to survive for so long — not a week or a month or a year or a decade, but 27 years! — puts his crimes in a new perspective. So does his apparent complete honesty when admitting to them. He made no excuses. He did not beg for leniency. He was completely open about his crimes. I, like Hughes, found it difficult to maintain any anger toward Knight, though others on the pond — victims of Knight’s break-ins — were able to.

Knight’s ability to survive for so long — not a week or a month or a year or a decade, but 27 years! — puts his crimes in a new perspective. So does his apparent complete honesty when admitting to them. He made no excuses. He did not beg for leniency. He was completely open about his crimes. I, like Hughes, found it difficult to maintain any anger toward Knight, though others on the pond — victims of Knight’s break-ins — were able to.Of course there can’t be a world full of people like Knight. Then again, there is no danger of that. You can say many things about Knight, good or bad. But it’s hard to deny that he is utterly unique.

Kenny: One of my favorite parts of the book was hearing Christopher’s literary assessments of nature writers like Thoreau and Frost. It really won me over. Are there any other of his literary anecdotes you can share with us that didn’t make the book?

Michael: I loved Knight’s literary criticism! There was something pure and amusing about it, untouched by academia. Here are a few tidbits that didn’t make the book:

Knight about the New Yorker magazine: “It’s not worth the cover price. There’s one good story per two or three issues. I still took them. But too many people trying to justify having a degree in English lit publish in the New Yorker.”

And, donning his music critic’s hat, here is Knight’s take on John Lennon: “If I ever met John Lennon, I bet me and him would get along great. But his fans — they grate on my nerves. They’re obnoxious. Baby boomers made such an idol out of John Lennon. That drives me crazy. Beautiful people so fiercely defend John Lennon that I don’t like him. It’s kind of sad. I can’t like John Lennon because of his fans. That’s why I don’t like Jack Kerouac either.”

And, donning his music critic’s hat, here is Knight’s take on John Lennon: “If I ever met John Lennon, I bet me and him would get along great. But his fans — they grate on my nerves. They’re obnoxious. Baby boomers made such an idol out of John Lennon. That drives me crazy. Beautiful people so fiercely defend John Lennon that I don’t like him. It’s kind of sad. I can’t like John Lennon because of his fans. That’s why I don’t like Jack Kerouac either.”Kenny: I admit to finding his eating habits striking to say the least. You note that it was as though the palate of a child was frozen in time. Are there elements of his person which were frozen in that manner during his 27 years of being a hermit?

Michael: In many ways, Knight is a teenager frozen in time. He certainly did not have a single conversation with another person between age 20 and 47. That’s the heart of your life! Knight never received advice or guidance from an elder, or had the opportunity to observe how adults are expected to behave in society.

Considering this, it was surprising how well Knight was able to interact with me. But his occasional petulance, his emotional vulnerability, his lack of a “little white lie” mechanism, his belief that he needs no guidance from anyone older than him — all indicated a personality that had been undeveloped since he left the world behind, in 1986.

Kenny: As someone who lives close by to North Pond I must say that Christopher’s ability to manage Maine winters outdoors, not to mention mud season, really is remarkable. You favor the outdoors yourself. What did you learn from him?

Kenny: As someone who lives close by to North Pond I must say that Christopher’s ability to manage Maine winters outdoors, not to mention mud season, really is remarkable. You favor the outdoors yourself. What did you learn from him?Michael: As an avid outdoorsman who spends a lot of time in Montana, where there can be extremely cold weather, I was fascinated by the details of Knight’s survival in the Maine woods. I loved this bit of insight especially: “It’s better to stay dry than warm.” I’ve repeated that to myself on some recent cold-weather trips, and it’s become a sort of outdoor mantra of mine. Knight’s struggles with keeping his feet warm were also interesting to me — I’ve had many of the same issues.

I was also amazed by Knight’s cold-weather regimen of getting up at 2 a.m. so that he was awake and moving at the very coldest weather — that’s counter-intuitive (when it’s truly cold most people want to cocoon in their sleeping bags) and also very wise. Without that rule, it’s extremely likely that Knight would have frozen to death. I hope I don’t ever have to enact such a rule during one of my outings. When I camp in cold weather, I tend to have a fire — quite often a big one.

Kenny: Thanks so much Michael. We’re looking forward to your book launch here in March.

Michael: I’m really looking forward to it myself.

I actually live on North Pond in Smithfield, growing up it was always kind of a urban legend about the hermit. I enjoyed this book very much, it was fascinating from many different views. Truly because when he talked of the lake I knew exactly what he was talking about, I didn’t have to imagine it I live here. I never once felt anger towards him, we all have to much stuff anyway. I did admire him and the way her didn’t care what anyone thought of him and escaped societies claws. He truly is very unique and a one of a kind.

I got this book at NEIBA and it’s really great. It’s a rare and lovely thing when a book is both an easy sale for regionality but also is really well written.