For several days now I’ve been waiting for inspiration to strike and tell me what to post in honor or celebration or at least recognition of the new year. Do I quote from a book about new beginnings? Do I share some quirky list of reading-related resolutions? Recap the highlights of the past year in books? Review something? Relate something? You see my dilemma.

At the eleventh hour I’ve come up with this: great writing. I want to give you great writing, as a reminder of why it is that we’re all in this crazy business of books, and why it is that reading is such a delight, such an indescribable pleasure when the words are right and the writer is even more so.

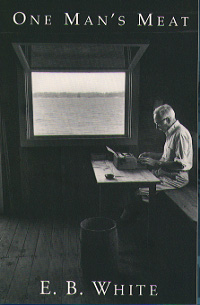

I’ve had no trouble settling on WHAT writing to share with you, as there is one book that I’ve fallen more in love with this past year than I have with any other (and oh, there have certainly been others). The book I’m referring to is not written for children, but it does feature writing by a man who wrote, without question, some of the finest books ever written for children. And, as I discover anew each time I read another book or essay or letter, he penned, some of the best material ever written for adults. I’m referring, of course, to E. B. White. And the book I’m about to quote from is a collection of his essays called One Man’s Meat (Tilbury House, 1942) — the book I was happiest to add to my home library in 2007.

First, a selection from White’s essay called "Progress and Change" published in Harper’s Magazine in December 1938, soon after White had relocated from NYC to North Brooklin, Maine. I’m including it just because I think it showcases White’s writing so incredibly well:

My friends in the city tell me that the Sixth Avenue El is coming down, but that’s a hard thing for anyone to believe who once lived in its fleeting and audible shadow. The El was the most distinguished and outstanding vein on the town’s neck, a varicosity tempting to the modern surgeon. One wonders whether New York can survive this sort of beauty operation, performed in the name of civic splendor and rapid transit.

A resident of the city grew accustomed to the heavenly railroad that swung implausibly in air, cutting off his sun by day, wandering in and out of his bedchamber by night. The presence of the structure and the passing of the trains were by all odds the most pervasive of New York’s influences. Here was a sound that, if it ever got into the conch of your ear, was ineradicable — forever singing, like the sea. It punctuated the morning with brisk tidings of repetitious adventure, and it accompanied the night with sad but reassuring sounds of life-going-on — the sort of threnody that cricket and katydid render for suburban people sitting on screened porches, the sort of lullaby the whippoorwill sends up to the Kentucky farm wife on a summer evening.

(Leaves you wanting more, doesn’t it? So go get a copy of the book!)

Next, a paragraph from "Compost" published in Harper’s Magazine in June 1940, included here because I like both White’s message and (of course) the way he delivers it:

The way to know the shape of things in advance is to listen to seers and mystics instead of economists and tacticians…. Part of the preparation for the perfect world society will be the recognition of seers. It will be required of the President of the United States that he read one poem and one parable or fable a day, in addition to the editorials in the Times. The brotherhood of man can never be achieved till the democracies realize that today’s fantasy is tomorrow’s communiqué.

And, finally, a couple paragraphs that rang (somewhat painfully) true for me this past weekend, as I tried to get a jump on marking catalogs and reading f&g’s in preparation for January and February’s onslaught of appointments with sales reps. These two paragraphs appear at the very start of White’s essay called "Children’s Books" published November 1938 in Harper’s Magazine, seven years before White would write children’s books of his own:

Among the goat feathers that stick to us at this season of the year are some two hundred children’s books. They are review copies, sent to my wife by the publishers. They lie dormant in every room, like November flies.

This inundation of juvenile literature is an annual emergency to which I have gradually become accustomed — the way the people of the Connecticut River valley get used to having the river come into their parlor. The books arrive in the mail by tens and twenties; we live with them for a few crowded, fever-laden weeks and then fumigate. Lacking shelf space, we pile them everywhere — on chairs, beds, davenports, ledges, stair landings. Some of them we tuck away in spidery cupboards, among the crocks and fragments of an older civilization. Turn over a birch log on my hearth and you won’t find a beetle, you’ll find Bumblebuzz, the chronicle of a bee. Throw open the door of our kitchen cabinet, out will fall The Story of Tea. Pick up a sofa cushion and there, mashed to a pulp, will be a definitive work on drums, tomtoms, and rattles. For the past three weeks I have shared my best armchair with the Boyhood Adventures of Our Presidents and a rather heavy book about the valley of the Euphrates. Mine is an uncomfortable, but not uninstructive, existence.

Here’s wishing you a year that’s comfortable, instructive, and filled with wonderful writing.