Diane Magras is a middle grade author with the gift of writing books with real heft and dimension within a breakneck adventure story. Her newest book manages to incorporate some of her established strengths and interests and weave them into a wholly different setting. I knew from spending a pre-pandemic day with Diane in area schools that she had real command over the historical dimensions of her books and was not surprised to see her evidence that same command over the fascinating world she set her terrific new book in.

Kenny: In Secret of the Shadow Beasts you adapted the strong affinity for medieval settings and weaponry you displayed in your two Madwolf’s Daughter books, into a modern environment with a gaming element. The pandemic has been all about adaption. How do you think young readers will connect with that element of the book?

Diane: I consciously slipped in some medieval elements (especially with characters who love medieval history, as I do), but a lot of readers will see the major medieval-like elements of the story—the Orders that the kids belong to, as well as the weaponry—as part of a gaming world. I was certainly thinking about what gaming was doing for people during the pandemic. For many, gaming was a way to escape a stressful world, to have power and agency at a time when they felt very little of that in real life. That holds true for my protagonist, Nora, who uses gaming as a way to survive her father’s death. The agency that comes from gaming was a big part of my inspiration, and I think that’s the big adaptation in real life that kids especially saw: they could build, battle, and survive (or come back at a spawn point) in this remove from the real world, a world that gained new meaning when all else was bleak. I wouldn’t be surprised if many young readers relate to that.

Kenny: The idea of separate ballads strung together in a particular order to produce a single, gestalt piece of music is a wonderful notion in the book. Lovecraft, however, suggested in writing that “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.” Are Lovecraft’s notion and the sublime ballad put together and played by Nora’s father related?

Diane: Lovecraft is talking about greater awareness, and that’s actually a big theme of Secret of the Shadow Beasts—but in a positive way. By having a better understanding of our world, we are better able to deal with its problems, though we may find ourselves shaken to our cores. “Castle in the Sky,” Owen Kemp’s fiddle piece has deep emotional meaning and a strong healing element. By playing fiddle and creating tunes throughout his life (his work is based on traditional Shetland fiddle music), Owen processed his world. As the years went on, his pieces became faster, more complicated, and more profound, all speaking to his struggle during a difficult period in his life. Originally, each piece was a part of his trauma and recovery, representing key moments: betrayals, awakenings, escapes, and hope. By sharing them with his daughter, he was sharing his past. But unlike Lovecraft’s vision, by linking these pieces together, Owen created a whole new work that had the power to strengthen its player. I see the revelation of the whole piece as majestic, hopeful, and ultimately healing.

Kenny: The idea of kids being put at risk to protect adults is always a powerful inversion. How did you approach it in your new book?

Diane:I hope it’s an inversion that kids will enjoy. How often are they literally the only ones who can save the world, and recognized as such by their society?

That said, I was keenly aware that this inversion might be a challenge for some adults. “What kind of world would send their children out to fight monsters?” they might ask. And they might wonder about the moral choice made by this world, akin to Ursula K. LeGuin’s question about utopia: What are you willing to do to the few for the good of the many?

Yet I wanted this to be a moral world, not a society with a corrupt and uncaring government. It’s simply a world stuck in a horrible situation. As I mentioned above, the only ones who can save humankind are the children. Shadow beasts pause before they attack children (they don’t pause for adults), and children who can handle the monsters’ venom can use that pause to defeat them. This government has tried many other methods, but this has been the only method that works.

This government also does everything they can to keep children safe. They train only a small number of children from a very young age to be ready for battle—in body and mind—with mental health services equal to the physical training. By the time these kids go out to fight, they’re not risking their lives: They’re highly trained professionals who know what they’re doing. Those who are not ready simply don’t fight, as the Director of the National Council for the Research and Destruction of the Umbrae tells one of my characters. And in that sense, I neatly sidestep the moral question. Unless the young warriors themselves take chances or don’t follow their training, they’re actually reasonably safe out with the monsters.

Kenny: Acknowledging that some people consider childhood itself a modern invention, was there anything like a gaming equivalent for medieval youth?

Diane: Childhood was actually a treasured part of medieval youth: a time to learn, play, experiment, and grow (though it ended a lot sooner for many people). Video games themselves could have two parallels with medieval games. RPGs based on action would be a lot like imaginary games of warriors and battle (and for kids of noble birth, it would be actual practice with wooden swords and targets). For the lore that is such a crucial part of gaming these days, I’d point to storytelling. Relating legends and stories was a huge part of medieval life: in lessons shared by family, through the church, or heard by the fire at celebrations. Children would have heard these stories year after year, and learned to embellish and share these stories themselves.

Kenny: Large corporations are being understood more and more as assuming the roles in its workers’ lives traditionally filled by religion and social and sporting clubs. How does The MacAskill Corporation seem to fit into that societal development?

Diane: MacAskill’s organization is actually a wing of the government of Brannland: the National Council for the Research and Destruction of the Umbrae. They exist not as a for-profit but as a high-level agency that aims to protect its citizens—but I can see the similarities you mention. Its public wing offers research-based advice on Umbrae behavior, as well as health-based advice, including what to do if you’re bitten, with free antidotes distributed annually and on-demand. The private element brings together children on a voluntary basis to train to battle the Umbrae. But here’s the thing: No one particularly wants child soldiers. It’s just that no one else can stop the Umbrae. And so the National Council trains the children carefully, with research-based practices, to ensure that they’re prepared once they’re sent into the field. When they’re not in the field, they receive everything they need—from mental health services to familiar foods from their childhoods to a library designed for their reading levels and interests. People within the National Council have been involved in this work for most of their lives—former knights who age out of fighting often become staff—and so it’s a tight-knit family too. Each generation thinks about what went wrong and what they needed, and makes improvements in the care for the next. I saw this as a model for how a society in desperate straits could create a healthy, positive world.

Kenny: If you were going to recommend books for your protagonist Nora to read that might help her with the challenges she faces, what would they be?

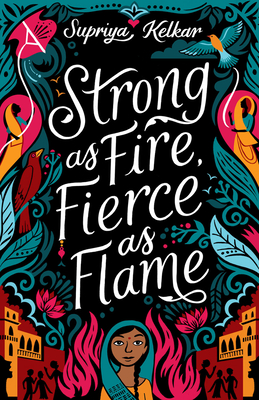

Diane: Nora needs to think about the truth that hides within our narratives of history, and how we might stand against oppression. I’d give her Supriya Kelkar’s wonderful historical novel Strong as Fire, Fierce as Flame to ponder that. She also could use a narrative about how kids can survive impossible odds, and what’s beautiful about life when you have nothing; I think she’d enjoy and learn a lot from Geraldine McCaughrean’s Where the World Ends. For a warm story about trauma and healing to help with the trauma Nora carries, I’d add Niki Smith’s graphic novel The Golden Hour to her stack. And for team-building among people who aren’t quite your friends, Rajani LaRocca’s Much Ado About Baseball would be a delightful read and give her some useful tips!

Kenny: Thanks Diane!

Diane: My Pleasure. Thanks for the thoughtful questions.

Pingback: - Diane Magras