The Woman on the Windowsill is that rarest of crossovers, an academic history book with broad and immersive appeal to a wide range of general readers. Lovers of history, mystery, thrillers, women’s issues, gender politics, true crime, or young adult, will all leave its pages richer than they entered them. It is centered on a set of real-life lurid plot elements which any self respecting intellectual thriller or true crime book would be ravenously eager to possess. A series of corpse mutilated body parts were anonymously put on public display. First, a pair of women’s breasts set on a lily pad and then left on the windowsill of a well to do citizen’s home in full public view. Days later the breasts ere followed by a pair of hands, then a pair of ears, and finally a pair of buttocks.

You may be asking yourself why an academic book is the subject of a children’s book blog post. There are two reasons. First it is a sensational and unusual book which everyone should read. Second, its author, Sylvia Sellers-Garcia, is a history professor at Boston College by day and a prominent middle grade and YA fantasy author, writing under a pen name, by night.

What makes the book a special treat is that Sellers Garcia’s literary flair, so marked in her alter ego’s books, is quietly evident throughout this scholarly work so that wonderful observations and turns of phrase greet us like unexpected but welcome guests materializing on the streets of a foreign city on a trip whose narrative contours and intricacies reflect the excellent and deft touch of a gifted novelist.

This striking instance of corpse mutilation occurred in the year 1800 in Guatemala City. In casting her attention on it Sellers-Garcia unpacks a viscerally absorbing exploration of violence against women, marginalization, historical erasure, tensions between science and theological perspectives, sexual mores, race and class issues, medical politics, and the evolving nature of police states. The book is charged with contemporary interest and yet the effectiveness of its its exploration involves a philosophical argument and practice regarding the nature of the relationship between contemporary interest and the past.

The Woman on the Windowsill forcefully argues that the acuity of the present depends on the integrity of the past. The more strenuous an effort is made to understand the past in its own terms, the more relevant and illumining it becomes to the present moment. Presentism, the projection of the present onto the past, undermines our understanding of both past and present.

No book more forcefully demonstrate this principle than The Woman on the Windowsill. In its strenuous effort to understand a series of bizarre and lurid crimes in their original context, Sellers-Garcia succeeds in expanding our understanding of core elements of the erasure and ancillary violence against women that has both endured and evolved over time.

The case at the the center of the book raises a series of interrelated questions. Who was the woman whose corpse was dismembered? The act was clearly intended to convey a message. What was that message? How was the nature of the crime understood at the time in economic, political and social contexts? How was someone able to do this undetected in a bustling urban center? What does the extant evidence of the police investigations, judicial records, and medical records tell us? How did people in 1800 Guatemala City understand the relationship between life and death and sex and death? Who was the perpetrator?

Sellers-Garcia addresses these questions with an engaging combination of an historian’s discipline and a novelist’s eye for detail, narrative and style. Time travelers have a unique perspective on the contemporary world they return to, and The Woman in the Windowsill is a lively guided trip back to the streets, houses, morgues, and hospitals of 1800 Guatemala City. Sellers-Garcia’s disarming use of first person greets and centers the reader upon every juncture and crossroads in her investigation. In directly revealing each set of various possibilities, along with her own substantive inclinations and biases, she engages the reader in a dynamic conversation free of allegorical constraint.

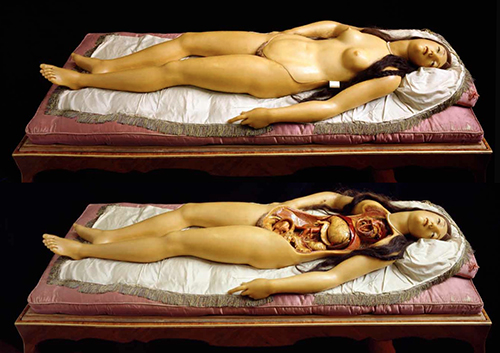

The book is filled with wonderful fragments and scenes of the past. We encounter wax anatomical Venuses, which are incredibly intricate and even sensual, though used in lieu of actual dissection. We meet a dedicated, class conscious, enlightened, overworked doctor who somehow found time to relentlessly pursue and stalk a well to do an uninterested widow. We also encounter a young woman who escaped her overbearing, and abusive mother though a hole dug into the floor under her bed and many other equally fascinating glimpses seen through the incidental windows into personhood afforded by archival records which were intended for official purposes.

There is a wealth of intellectual history involved as well. The clear intent of the display of corpse mutilated pairs of a woman’s body was to send a message, for example. The nature of that message, however, poses a mystery to modern eyes and the author leads us on a fascinating consideration of potentially relevant iconography, including some very salty anti-clerical and anti-religious proclamations from the period.

Sellers-Garcia makes a number of very clear points. It was physically dangerous to be a married woman. The erasure of women is their most visible attribute in the archives of the period. Concepts of sexual crime, and crime in general in pre-Freudian 1800 Guatemala City involved distinct notions of public and private actions in which right and wrong were understood strictly through the filter of negative impact on the social order. In 1800 Guatemala City if a tree fell in the forest and no one heard it, then it not fall.

As we journey through The Woman on the Windowsill our immersion in another time and place brings with it an acute sense of perspective on the constants and variables which accompany the sadly gangrenous aspects that attend the human social enterprises of politics, gender politics, personal sovereignty, police power, class and race. The integrity, candor, incisive interpretation, and narrative flair of this book carries with it a momentum that impels us see our own world with an historian’s eye, to embrace critical understanding and to step away from the reflexive erasure of what offends us.

Informed engagement is an agent of positive change even, and perhaps especially, when that means understanding where we need to respect the limitations imposed by the erasure and extant contours of the past. As Sellers-Garcia puts it. “It’s significant — painfully significant — that we don’t know more about these women and their “ordinary” lives. Whether we know about them makes no difference to their importance in their own moment, but knowing or not knowing makes quite a difference to us. The characters who people the past matter to how we see it…. That erasure is genuine; I would not wish to lessen it or, worse, to ignore it. We can look into their lives, catching glimpses through the muddled pane. But we also have to accept that these are only glimpses. And then we draw back, and move on, and the shutters close.”