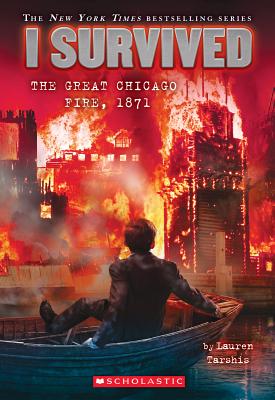

Children in fourth, fifth, and sixth grade take an active interest in the real world. If you were to poll a group of fourth graders as to what books they were reading you would find nonfiction based series such as I Survived and Who Was/Is contending with the might of Wimpy Kid  and Dogman for popularity. This is because middle grade readers are very interested and engaged indeed in clarifying the nature of things. Lucretius himself would find them estimable.

and Dogman for popularity. This is because middle grade readers are very interested and engaged indeed in clarifying the nature of things. Lucretius himself would find them estimable.

Having gotten the macro stuff, that Santa, the Tooth Fairy, dragons and trolls are imaginary, middle grade readers want to explore things with a finer lens. It’s complicated: for example, robots are real, but space robots visiting from other planets are fictional. Even their aforementioned guidebooks to the nature of the real world, nonfiction books are nuanced, and interwoven with fiction. The I Survived books insert the fictional element of child protagonists into their accounts, for example.

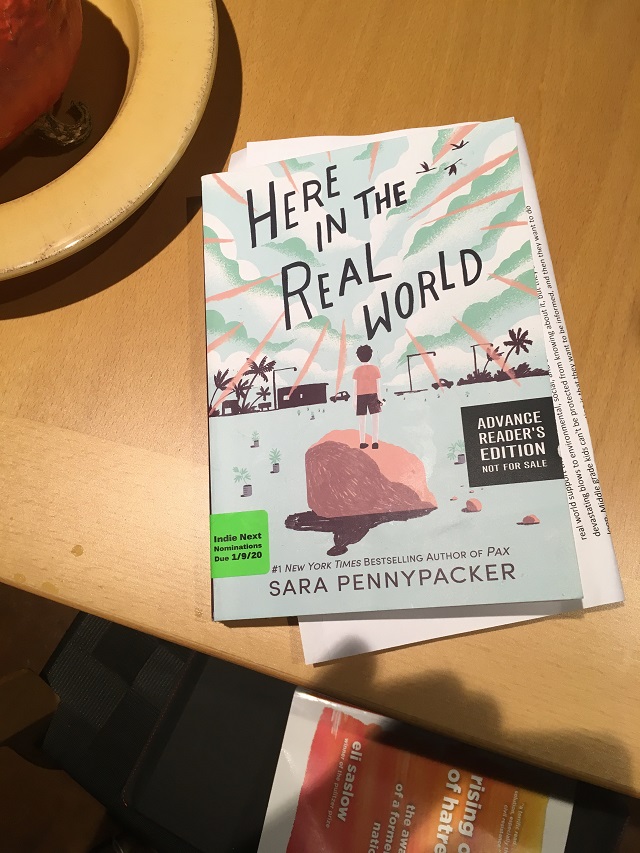

What of human nature, though? The issue of how much middle grade books should tell it like it actually is as opposed to how it would be in a slightly more rational, supportive and hopeful world has been coming up more and more lately. Pax author Sarah Pennypacker addresses it notably and head on in her new novel Here in the Real World.

Our central question is, does the intrinsic interest middle grade readers have in sussing out the nature of the real world support the following statement Pennypacker included in her note to readers in the ARC edition of Here in the Real World? “These days, devastating blows to environmental, social, and economic justice seem to play out in an endless media loop,” she wrote. “Middle grade kids can’t be protected from knowing about it, but they don’t want to be, anyway, because they care. My observation is that they want to be informed, and then they want to do something.”

Personally I do not believe it is that straightforward a situation, neither among individuals nor even in the same individual. To answer our question I believe it is important to bear in mind that middle grade readers have a foot in at least two worlds. For example, middle grade readers fluctuate day to day. One day they want to step ahead and nip a copy of Dear Martin from their older sister’s room. Another day they just want to curl up in the familiar comfort of an animal fantasy like Warriors. They have a toe over the coming of age line but they are not going to cross it. They are in a state of progressive suspension in which moral and intellectual flashpoints can subtly shape who they are and will become. Hence the power of a great middle grade book.

Personally I do not believe it is that straightforward a situation, neither among individuals nor even in the same individual. To answer our question I believe it is important to bear in mind that middle grade readers have a foot in at least two worlds. For example, middle grade readers fluctuate day to day. One day they want to step ahead and nip a copy of Dear Martin from their older sister’s room. Another day they just want to curl up in the familiar comfort of an animal fantasy like Warriors. They have a toe over the coming of age line but they are not going to cross it. They are in a state of progressive suspension in which moral and intellectual flashpoints can subtly shape who they are and will become. Hence the power of a great middle grade book.

It is also important to note that there is a qualitative difference between reading up about issues and the nature of humanity and being directly addressed about them. When a precocious 10 year old reads A Fault in Our Stars she know that the audience is not her but older kids, which grants some essential flexibility and suppleness. When a middle grade book deals with issues and the nature of the human condition she is directly the audience, and is more captive to the narrative.

There are two primary norms for dealing with tough issues in middle grade fiction. One is immersing the issue within a compelling fantasy or adventure story. A good book or series has both a fun and compulsive narrative stream and an eddy in that stream in which issues gather and slowly develop. Flashpoint issues embedded in a such a way allows middle grade readers to engage with or step-over them depending on the day they hit that page. If handled deftly in this manner an issue in a middle grade book can have enormous impact despite being a secondary aspect of the story put forward in an opt-in manner.

The second norm is to deal directly with the issue, but to carefully manage its content and intensity, infusing the story with far more hopefulness, justice and responsiveness than one would ordinarily encounter in realistic fiction. This approach allows the young reader to step in and out of issues, having learned about and engaged with them in a safe space with the freedom to incorporate their engagement from whatever point of view their own life experiences, personalities, and dispositions call for.

In Here in the Real World, Pennypacker argues for a third norm, that of presenting the world exactly as it is and following the Dark Knight’s dictum that “the world sees sense only when it’s forced to.” The story makes the tension between the real world and one seen through rose-tinted lenses its very center. The book has two main protagonists, Jolene and Ware. Jolene, a girl abandoned by her mother and raised by an aunt who is neither a nurturing nor a competent caregiver, has had a two-pronged response to having been treated like trash. First, an absorbing interest in recycling and second, a core belief that “in the real world, bad stuff happens.” Ware, a boy who struggles to integrate socially, and prefers to live in a chivalrous world of his own making, believes strongly in fairness. Jolene continually asserts that Ware lives in “Magical Fairness Land.” As she is wont to tell Ware, “Maybe in Magical Fairness Land the right thing happens. But not here.”

Throughout the book this tension is explored as Ware and Jolene seek to preserve a semi-demolished church from being sold and converted into a mini strip mall. The lot has become a special place for both of them. Jolene is using its grounds to grow papaya trees in order to sell their fruit and fend off the eviction from her apartment that her aunt’s bad habits are tending towards. Ward has converted the ruins into a castle. In the end, as Ware fights a a gallant but losing battle to preserve the lot, he comes to see that the little things people do to make the world more fair are part of the real world too.

Interestingly Pennypacker wraps Jolene’s stark philosophy up with a good deal of magical fairness. Her friend and benefactor, the owner of the Greek Market, has made retirement plans which include both returning to Greece and giving the market away to Jolene. Ware wins the ownership of his family’s backyard from his parents and turns around and gives it to Jolene and her displaced papayas. In the end all their efforts to save the lot, though they come up short, bring together a disparate community, save a whole bunch of migrating birds and a turtle on the extinction list, forge lasting friendships, give Ware an awareness of being an artist with a social justice purpose, and return holiness to the ruined church. In short the story supports it’s stark premise with a huge dollop of hope, justice and magic.

Interestingly Pennypacker wraps Jolene’s stark philosophy up with a good deal of magical fairness. Her friend and benefactor, the owner of the Greek Market, has made retirement plans which include both returning to Greece and giving the market away to Jolene. Ware wins the ownership of his family’s backyard from his parents and turns around and gives it to Jolene and her displaced papayas. In the end all their efforts to save the lot, though they come up short, bring together a disparate community, save a whole bunch of migrating birds and a turtle on the extinction list, forge lasting friendships, give Ware an awareness of being an artist with a social justice purpose, and return holiness to the ruined church. In short the story supports it’s stark premise with a huge dollop of hope, justice and magic.Here in the Real World, apart from having great values, and being very moving indeed, underscores the real complexity hidden within its own simple message. You see, in the real world middle grade readers do sometimes want to know what the world is really like, but when they do they need as much magical fairness as can be had. Other times they just want a great magical adventure that will stand them in good stead when they have to deal with real world issues down the line. Happily Here in the Real World fits both those descriptions.