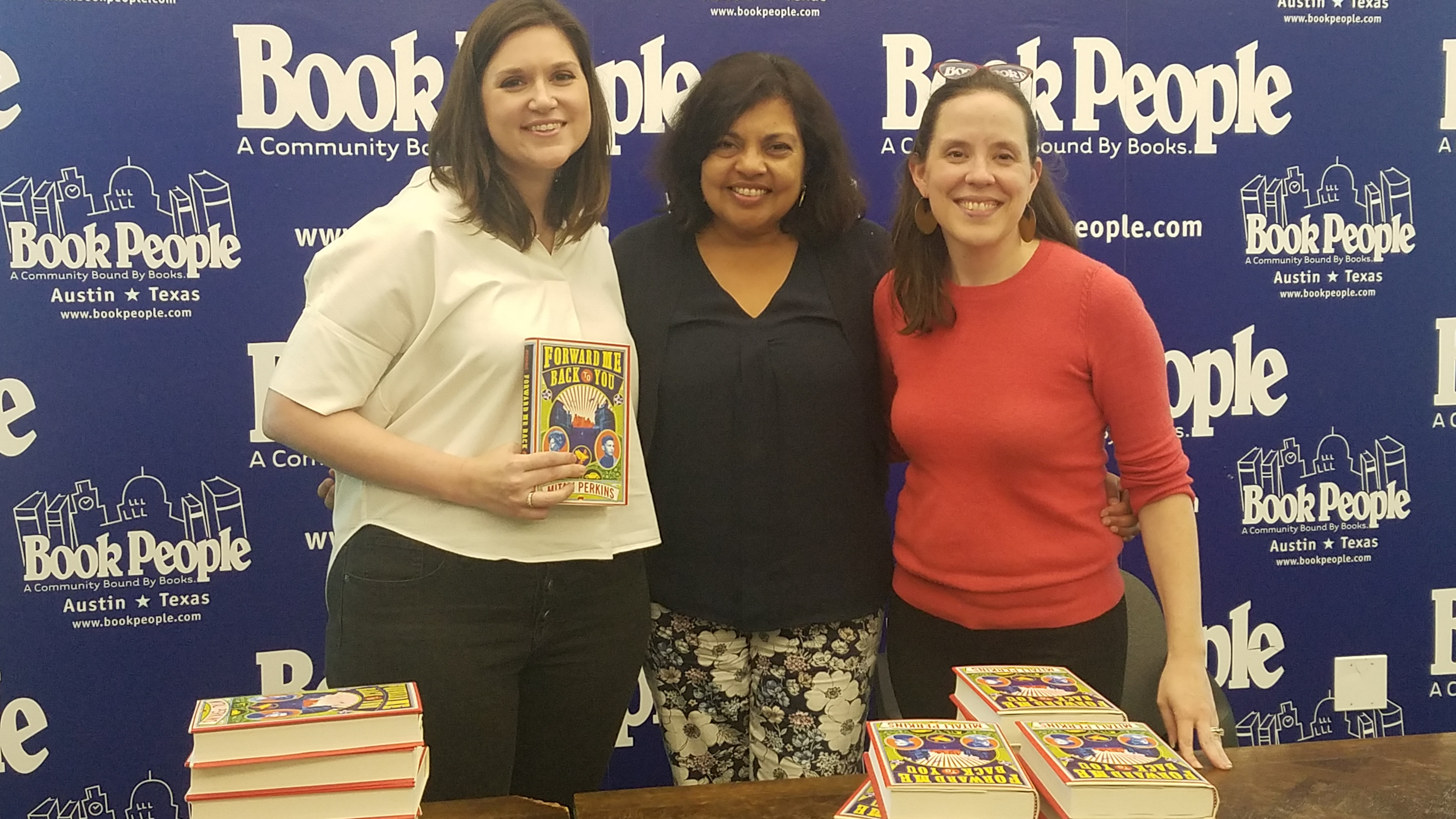

We were lucky enough this month to host Mitali Perkins for her new book Forward Me Back to You. She was in town primarily for school events, and we invited her to join us for a special conversation with educators to talk about her book with the Anti-Defamation League through the lens of their landmark No Place for Hate® program. Designed to help educators build inclusive, respectful environments where every student can thrive, the program has been implemented in all Austin area schools. We’ve done a few of these author receptions for participating educators now, first with Jewell Parker Rhodes, then Erin Entrada Kelly, and now Mitali Perkins, and I love them. They’ve all been different, but each one has produced truly thoughtful  discussions about the power of books to expand necessary conversations; navigate complex territory; and build caring, confident, culturally literate readers.

discussions about the power of books to expand necessary conversations; navigate complex territory; and build caring, confident, culturally literate readers.

With a background as a school counselor and a passionate commitment to building empathy and combating bias in our schools, ADL Austin’s Education Director Jillian Bontke is one of my favorite moderators because she reads with her heart wide open and dives right into the messy human dynamics that make stories like Forward Me Back to You resonate so deeply—qualities that made her a wonderful partner for Mitali Perkins who always wears her literary heart on her sleeve (and in person is much the same). The conversation that followed was a passionate and slightly tearful exploration of family, identity, community, and advocacy.

Raw and deeply emotional, the novel follows two teens struggling with personal crises: Kat, a 16-year-old reeling from an attempted sexual assault; and 18-year-old Robin (born Ravi), yearning for connection with his Indian roots and struggling with feelings of loss for his first country and first family. Brought together by circumstance and a shared mentor, Kat and Robin head to Kolkata as volunteers to support survivors of sex trafficking. It’s a book about trauma and identity, family and the meaning of home, injustice and respectful advocacy. Along the way their American assumptions are challenged as they aren’t the saviors they hoped to be and answers to their questions prove tragically imperfect, but ultimately to me, it’s a book about searching—searching for healing, searching for meaning, searching for the connections that make us feel rooted in and empowered by our own identities.

Mitali mentioned she’s found a pervasive sense of loneliness in America because our emotional villages get so spread out. As someone who has lived in five states in my life, I can’t disagree. But her comment made me think about how books perform that function in our lives, creating robust literary villages for us to turn to and rely on. Inspired in  part by her own experiences in Kolkata and as someone who became a second mother to two adopted boys from India, Mitali says she nonetheless leaves the interpretation of her novel up to every reader to decide, which I found very refreshing. She told us about a letter she got from a girl in rural Iowa who read Secret Keeper seven times and loved it because the overbearing aunt in the book reminded her so much of her stepmother. The setting and specifics of the girl’s life couldn’t have been more different from Asha’s (the protagonist), but she strongly identified with the themes of freedom and control. The truth is we don’t always know what voice is missing from someone’s life until they find the one that means everything—which is, of course, the miraculous power of story. It’s also the power gained by giving every kid a chance to be seen and heard, like ADL and the educators in the room all work so hard to do.

part by her own experiences in Kolkata and as someone who became a second mother to two adopted boys from India, Mitali says she nonetheless leaves the interpretation of her novel up to every reader to decide, which I found very refreshing. She told us about a letter she got from a girl in rural Iowa who read Secret Keeper seven times and loved it because the overbearing aunt in the book reminded her so much of her stepmother. The setting and specifics of the girl’s life couldn’t have been more different from Asha’s (the protagonist), but she strongly identified with the themes of freedom and control. The truth is we don’t always know what voice is missing from someone’s life until they find the one that means everything—which is, of course, the miraculous power of story. It’s also the power gained by giving every kid a chance to be seen and heard, like ADL and the educators in the room all work so hard to do.

The stories of our world aren’t always easy, but we gain nothing by looking away from each other. At first glance Grandma Vee, a character who sees everyone and collects new friends everywhere she goes can seem like nothing but a warm, all-knowing stereotype. But as she’s fleshed out, what seems like a magical quality becomes something else instead: a coping mechanism born from tragedy and a conscious effort to put kindness into the world because it can’t be given to those who are lost. We also spend a a fair amount of time in the book with babies born out of horrific moments who are loved nonetheless. During her talk, Mitali suggested that our greatest contributions to the planet often emerge out of our deepest tragedies, a sentiment that can feel either demoralizing or inspiring, I guess, depending on your point of view. In the context of this story about two teens who bear indelible scars but think that healing tears could be their superpower, it feels a lot like the latter to me.

Building a Literary Village

Meghan Dietsche Goel - May 17, 2019

Leave a reply