The seasons pass (publishing seasons, that is) and we frontlist buyers cannot help but observe obvious trends in picture book as they appear before us in our buying materials. The Fall 2018 lists have two marked trends. The first one is books that convey the idea that we all have differences and we are all alike in having those differences. We find similarities in language, color, and dress, and we share other similarities with those who sound and look differently from us, curiosity, anxiety, the potential for an enriched and expanded belonging. The second trend involves books that seek to convey a meaningful context for the stark ills which trouble our world in the present: war, bigotry, prejudice, and other forms of dangerous misapprehension, exclusion, and violence.

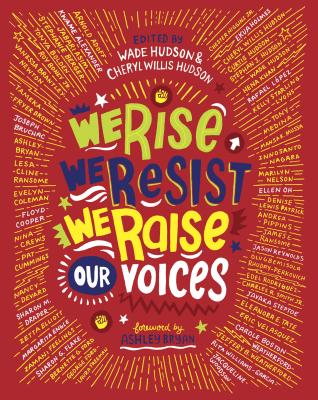

It is hardly surprising that the ills of the world, which are so engrossing and concerning for most of us right now, are front and center in the Fall frontlists as well. What we should tell children about the troubles of our time, their history, their present, and the means for their redress, is a timely preoccupation if there ever was one. It is the centerpiece, for example, of a major anthology being released this September, edited by Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson, We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices. For this book, 50 acclaimed diverse authors were asked to answer the question “In this divisive world, what shall we tell our children?”

It is hardly surprising that the ills of the world, which are so engrossing and concerning for most of us right now, are front and center in the Fall frontlists as well. What we should tell children about the troubles of our time, their history, their present, and the means for their redress, is a timely preoccupation if there ever was one. It is the centerpiece, for example, of a major anthology being released this September, edited by Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson, We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices. For this book, 50 acclaimed diverse authors were asked to answer the question “In this divisive world, what shall we tell our children?”

We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices is a powerful and timely tour de force, which invites readers to turn the central question on themselves both inwardly and outwardly. When I ask that question as a children’s book buyer and bookseller I reflect first on the fact that picture books are purchased by adults for children and seeing their own profound concerns reflected in these books makes sense from a retail perspective. The dual need for picture books to be meaningful, engaging, and wonderful for children remains the core of our question.

First let us look at Tolkien’s observation that “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned – with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.” Personally I think this is doubly true for picture books. Children are not, after all, “old and wary enough to detect its presence.”

There are a number of very important and complicated factors at work. The experiences of children differ wildly, of course. Some children are not aware of the world’s ills unless adults choose to share that information with them. Some children are being gravely harmed by choices made by adults. Between those two extremes lie a world of nuance involving race, class issues, and other biases. What a child would benefit from knowing and experiencing though a book depends in part on their own character and experiences and yet the manner in which a story is told greatly affects the width of its potential audience. Inclusion is a benefit in some form to any picture book reader, for example, while a depiction of the terror of war is not.

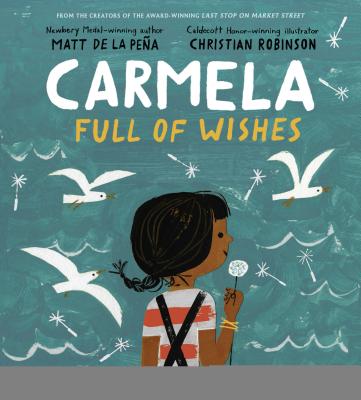

When confronted with difficulties children need story elements they can apply. Ideas, concerns and insights are most powerfully conveyed though great storytelling. The literary adage to show, not tell too often goes out the window when adults, seeking to ensure that children become the change the world needs, look to share books that are too overt and didactic. I have seen many books on the Fall lists that put forward the idea of being able to see yourselves in others who appear different from you in direct terms but none of them can hold a candle to Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s new Carmela Full of Wishes. Carmela conveys everything a well-meaning adult might wish along with worlds of varied applicability, engagement, and interest for any young reader who experiences the book. Tagging along with Carmela on that most important day when she is old enough to join her brother on his rounds is a journey, not a lecture, and that is where the magic is.

As we make decisions about what to share with children in picture books, and what children’s books to share with children, I always try to remember that they are one and the same question. Great, inclusive stories have the widest and deepest applicability to experience. Great stories are what every child needs, no matter how privileged or abused they are.

What Should We Share with Our Children?

Kenny Brechner - July 5, 2018

Leave a reply