It is my great pleasure to invite guest bloggers occasionally to my corner of ShelfTalker. I’m especially moved by today’s guest post by author Justina Ireland. She recently addressed a group of booksellers at the NEIBA Children’s Breakfast in Providence, R.I., speaking the powerful, beautiful words below. I asked Justina if we might share her speech with the wider audience of ShelfTalker readers, and she generously and unhesitatingly agreed.

I wish you could all hear Justina’s lovely strong voice speaking the words below, but as the next best thing, here is the written version of her talk, followed by a note on Justina’s books and what she’s currently reading.

Take it away, Justina!

***

Author Justina Ireland

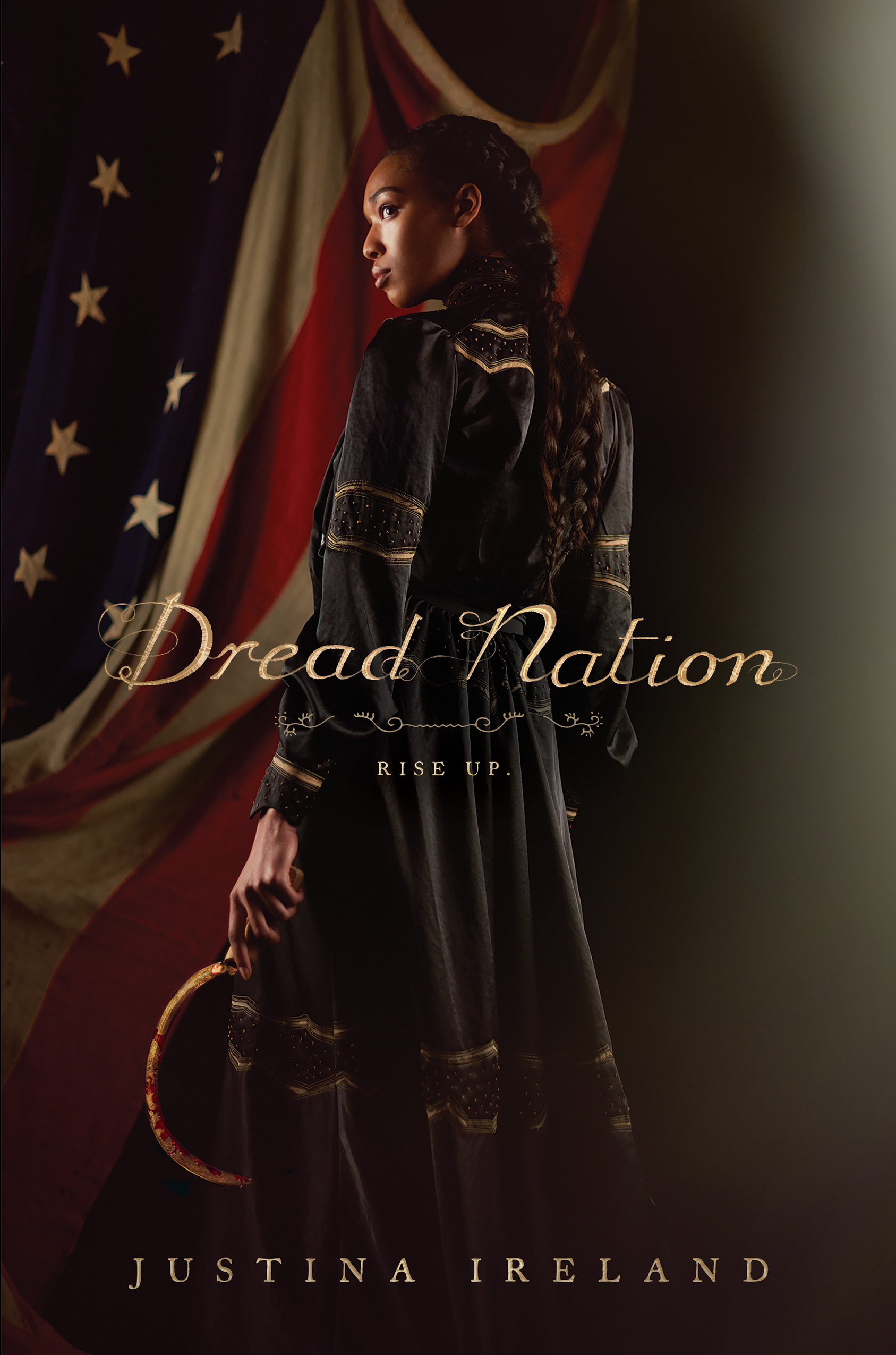

Hi, my name is Justina Ireland and I’m the author of Dread Nation. Thank you so much for inviting me to the Children’s Breakfast. It’s an honor to be here in the room where it happens.

So, today I’m going to talk about Dread Nation, because that is obviously the reason I’m here, but first I want to talk about one of my favorite books, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

I always get a little sad when I think about Huck Finn. I read the book for the first time in my sophomore year of high school, shortly after moving from my hometown of San Bernardino to Walnut Grove, California, a small town in the northern part of the state. My parents were getting divorced, and I had just moved from a busy, overcrowded high school with thousands of classmates to a country school where I was one of 83 sophomores. And the only black person in the entire school.

Of course, the first book we read as a class was Huck Finn.

Now, I went to school in a time before the updated version of Huck Finn. And we had a habit of reading chapters together out loud, which is a punishment for struggling and confident readers alike. So even though I loved hearing about Huck and his adventures on the Mississippi River, as we read through the story it was a bit like swimming in a beautiful lake full of piranha. Because every time I lowered my guard, there was a comment about how stupid Jim was, or how he couldn’t possibly be expected to be as quick-witted as this young boy, or there was the word nigger, like a slap in my face, being read aloud by one of my classmates while everyone cast me furtive looks.

And while, yes, as a reader we are supposed to understand that Huck is a somewhat flawed and unreliable narrator, that doesn’t matter when you feel like a book is simultaneously nourishing and killing your soul.

I think Huck Finn is one of those books that hasn’t aged well, but is valuable all the same. It is a beautiful time capsule of a book. An important piece of history, Huck Finn shows us what people, even those of a liberal mind, thought of the world around them at the time. The most important thing we can glean from Huck Finn, other than the fact that Missouri is full of ne’er-do-wells, is that no matter how much you do or say or accomplish as a black person, you’re never really as go od as the lowliest, most worthless white person next to you.

Now that I think about it, this is probably isn’t what most people get out of that book.

And that brings me to zombies, the undead, or as Jane, the main character of Dread Nation calls them, shamblers. Because who doesn’t love a sudden segue into horror?

I’ve always been fascinated by the subtext of horror tropes. The scholarship on the role zombies play in our canon varies, but they all seem to agree that zombies represent a deep mortal fear. There are some who say that they represent death and dread of decomposition, after all, the things that happen to our bodies after death are pretty freaking gross. Others state that the restless dead represent anarchy, and what happens when the rules fall by the wayside and we’re reduced to our most basic form, that of pure animalistic drives. And author Tananarive Due states that zombies represent the fear of Black people, a remnant from the time where slave owners feared that the people they tortured might find agency and repay them for their sins.

For me, the undead have always represented something that cannot rest, some unaddressed sin, an obstacle that the heroes cannot move beyond, a challenge that they are forced to face again and again. If zombies were Greek mythology, they would be the rock that constantly threatens to crush Sisyphus.

In the United States, the legacy of chattel slavery, and most especially the white supremacy and systemic racism that such a peculiar institution codified, is the undead. How could we be the land of the free when a portion of our population was in chains? How can we be the land of the free when a few of us are still disproportionately targeted?

Because we are talking about a population that still sees their options limited in numerous ways by the forces at play in the systems they navigate. Racism isn’t just about punishing people for looking different, it’s also about limiting their options to such a degree that that group of people no longer feels human, so that they start to believe, even if only subconsciously, that they are every bit as bad as their oppressors say they are.

And this lack of options brings me back to children’s literature. There are precious few Black girls living full and complex lives in children’s fiction. Black girls die for the hero’s second act turn, so that Katniss can go on to learn what it means to fight for a greater good. Black girls get to watch someone else get a happily ever after, again and again, but rarely get one of their own. Black girls

don’t get to go to Hogwarts, you see, they don’t get to lead a revolution, and if they do, they are white when the movie is cast.

And even when we get our own characters, their story is usually one of unmitigated suffering, as though the only narrative worth telling about Black people in America is one of tragedy. Honestly, I’m tired of dead Black bodies. In books, in movies, on the news. I feel like I’ve always been tired of seeing the suffering of Black people, like I came from the womb exhausted and weary, the knowledge that my worth would be measured in my labor and my pain imprinted on my psyche with my first breath.

And this is something most white readers don’t understand: how everything they want to do or be could rub up against the possibilities of what they are allowed to do. Because for them, and most especially in literature, the possibilities are endless. But for Black children they are either relegated to a supporting role, victims of circumstance, or completely nonexistent.

And let’s consider for a moment what kind of message that sends to white children who read stories and only see Black kids as sidekicks or occasionally as victims. How do the stories we tell our children inform how they see the world around them? If you believe every Black person you pull over is a criminal, every Black person you pull over will be a criminal. Our beliefs have a way of shaping

the world around us, for better or worse.

Just last month white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, demanding the protection of Confederate statues that were erected during the onset of Jim Crow as symbolic reminders to the Blacks of their proper place. And at this point if you can’t see the parallels between a zombie horde and a group of white supremacists I don’t know what to tell you. Because while some might see a group of Black people marching for equality as the scariest thing imaginable, the unchecked white supremacy that drives policy and undermines our Constitution is far more frightening. For all of us.

When I see those angry faces yelling hate I have to wonder what books they read as children, because no one gets through school without reading at least a few. Even if it’s only Huck Finn. And even if they didn’t read any books, they must have heard stories, because telling stories is a fundamental part of what makes us human. What kind of stories were told to them to make them think they deserve to be happy and free and no one else does? What stories shaped their way of thinking in such a fundamental way?

And I say: most of them. Maybe all of them. Stories have power. Don’t let anyone ever tell you any differently. And the stories we tell have a history of telling only certain people they matter. When we say Black Lives Matter, it’s because everything in our society, from our policing practices to our educational and justice system, tells us they don’t.

All of this is why I wanted to show a Black character confronting racism head on, both metaphorical and literal. And so Jane McKeene was born, a girl who at times appears larger than life, but at the same time is struggling just to exist, to find a way to be something in a world that tells her she is nothing, expendable, a tool, and barely more human than the shamblers that stalk the countryside. Jane must prove her humanity time and time again, the same way people of color must prove they are worthy as well. Worthy of great schools, worthy of opportunities, worthy of being Americans.

And while Jane might give readers of color a very necessary entry point into children’s literature, she also shows white readers that yes, Black girls can be heroes. Because Jane is fierce and undaunted, and she represents equality for everyone, not just the few. She is, as Commissioner Gordon might say, not just the hero we need, but the hero we deserve: flawed, angry, a girl just trying to do her best and desperately seeking answers in a world that has precious few.

And this is why I wrote Dread Nation. I wanted to write a story that would create space for Black boys and girls to exist. I want to expand the possibilities, so that everyone could see us as heroes in literature for a change. I want to write us into existence. I want that Black girl sitting in her sophomore class listening to people debate the merit of Jim’s humanity to have a rebuttal, a book she can fall into the pages of and feel safe. Because stories are how we tell ourselves, and each other, that we matter, and they’re how we look out into the world and say “See this? All of this? You can survive this. You can do this.”

Justina Ireland addressing booksellers at NEIBA. Photo: Alex Green.

I want to remind us, and everyone else who picks up my book, that we matter. That we are also worthy of our humanity. We are not the thing that goes bump in the night.

I hope you’ll read Dread Nation, and I hope Jane finds a place in your heart and on your shelf. Thank you.

***

[Elizabeth here again.]

This speech encompasses so much, so clearly. If you ever encounter someone who doesn’t truly understand why it’s vital for ALL children to see themselves in book-mirrors of possibility, agency, hope, and strength—and for white readers to look through those windows and really *see*—please consider pointing them toward Justina’s words.

Also, mark your calendars for next April 3, when Dread Nation (HarperTeen/Balzer + Bray) hits bookstore shelves! It’s got zombies, it plays with alternate history, it features a flawed, fierce, and fabulous heroine, and it is one wild ride of a powerful and passionate novel.

In the meantime, you can read Justina’s Promise of Shadows (Simon & Schuster), Vengeance Bound (Simon & Schuster), Feral Youth (multiple authors; Simon Pulse), and in December, her story in Three Sides of a Heart: Stories About Love Triangles (multiple authors; HarperTeen).

We asked Justina what she is currently reading that nourishes her soul, and she said, “I just finished The Cruel Prince by Holly Black and it was amazing. And right now I’m in the beginning of The Apocalypse of Elena Mendoza by Shaun Hutchinson.”

Thanks so much, Justina, for sharing your experience and powerful words with ShelfTalker.

Comparing Charlottesville’s white supremacist marchers to zombies is insulting. To the zombies!