The most important thing about being an ally to any cause that isn’t inherently one’s own is to remember to listen more than you speak. I’ve written a lot about diversity in publishing and children’s books in this blog over the years, and it has been a roller coaster of hope and frustration, progress and molasses. And while I sincerely hope my words have been more help than hindrance to the cause, it seems to me that maybe I could be most helpful by stepping aside regularly to share the microphone of ShelfTalker with my bookselling colleagues of color to hear a diversity of voices in this blog firsthand.

So — children’s booksellers of color, whether you’re a bookstore owner or a frontline bookseller, in receiving or order fulfillment or book fair sales or events coordination, if you’d like to write about children’s bookselling, we would love to hear from you. You can write about any children’s bookselling topic; your post doesn’t have to be about being a bookseller of color, but of course it can be. Please email me at ebluemle a t publishers week ly dot com to let me know you’re interested. I’ve been having some trouble getting emails at that address, so please also cc me at flying pig books at gmail dot com, with the subject header ATTN: Elizabeth. Thanks!

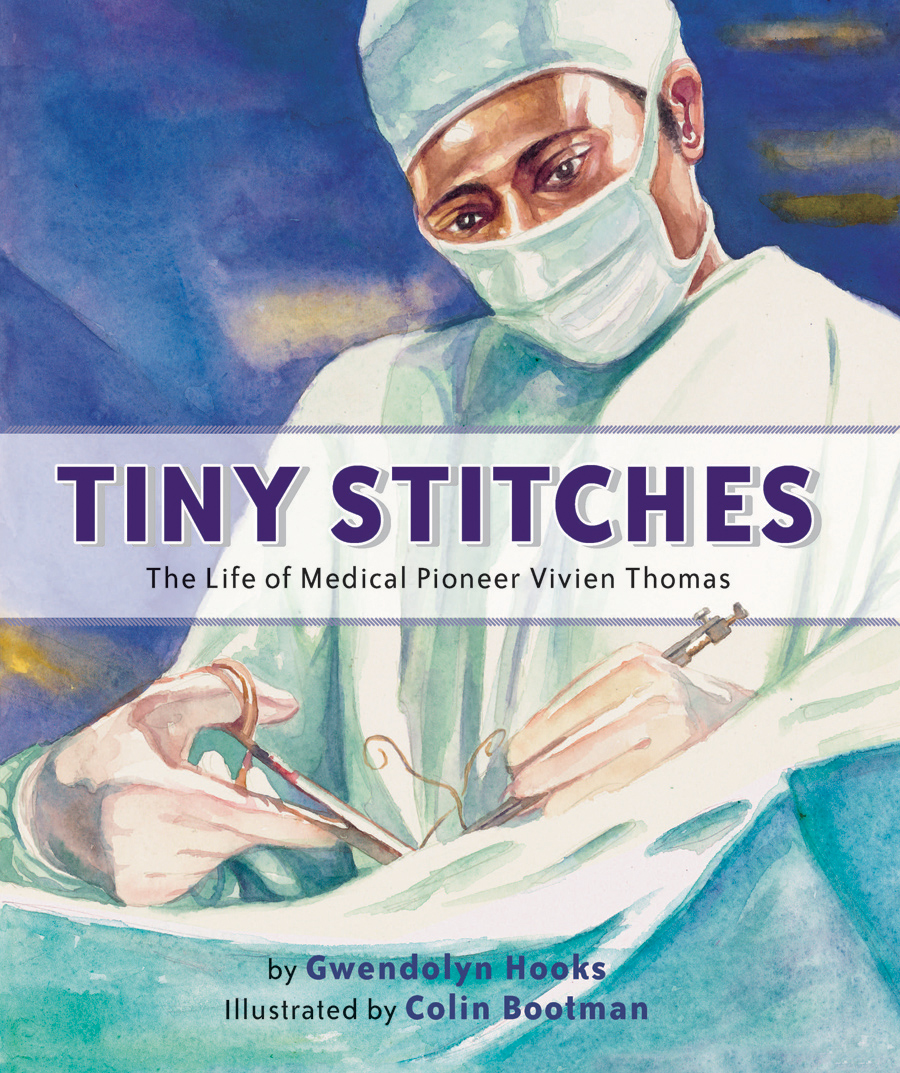

And in the spirit of celebrating a multitude of voices, I want to recommend a terrific recent picture book, Tiny Stitches: The Life of Medical Pioneer Vivien Thomas by Gwendolyn Hooks, illustrated by Colin Bootman (Lee & Low). The other day, my colleague Sandy asked if I had read this book yet. “It’s extraordinary!” she said. “My favorite new picture book!” Sandy has excellent taste, so I immediately grabbed a copy and read it. I was astonished to read about a medical innovator I’d never heard of, a Black doctor in the 1940s who pioneered successful open-heart surgery techniques on infants and babies.

And in the spirit of celebrating a multitude of voices, I want to recommend a terrific recent picture book, Tiny Stitches: The Life of Medical Pioneer Vivien Thomas by Gwendolyn Hooks, illustrated by Colin Bootman (Lee & Low). The other day, my colleague Sandy asked if I had read this book yet. “It’s extraordinary!” she said. “My favorite new picture book!” Sandy has excellent taste, so I immediately grabbed a copy and read it. I was astonished to read about a medical innovator I’d never heard of, a Black doctor in the 1940s who pioneered successful open-heart surgery techniques on infants and babies.

Despite the Depression taking all of his savings for medical school, Thomas never lost focus, instead becoming a research assistant at Vanderbilt University (though his official, utterly enraging, title was “janitor” because of the color of his skin). Thomas withstood a hideously racist environment, doing such accomplished research work that his white colleague, Dr. Alfred Blalock, refused to make a career move to Johns Hopkins unless they accepted Thomas. There Thomas weathered another racist work environment, along with low pay, difficulty finding housing for his family, and many other challenges. But his brilliance couldn’t be denied. When the hospital continued to lose “blue babies” due to a congenital heart defect, Thomas had an idea. He would redesign the surgical equipment in miniature, small enough not to damage the tiny hearts. He also designed the step-by-step procedure to repair the problem, sharing his ideas with Blalock and another doctor, Helen Taussig. Thomas’s years of research and work had led to an exciting, life-saving solution.

But racism reared its ugly head again. Though Thomas had designed both the equipment and the procedure, he was not allowed to do the surgery himself. Instead, he had to stand behind the white doctor, leading the surgical team through each step. It’s almost too absurd and insulting to believe, yet Thomas endured the situation with grace. The surgeries were a great success. Thomas had found a way to cure babies born with this heart defect. The procedure won awards and recognition — under Blalock and Taussig’s names. Thomas’s name wasn’t even mentioned in the report.

Vivien Thomas did at long last receive some recognition for his pioneering work, an honorary doctorate in 1976. I am so grateful for this picture book for introducing a whole generation of readers to an extraordinary medical hero.

Black Voices Matter – An Invitation

Elizabeth Bluemle - July 12, 2016

Leave a reply