Pax, Sara Pennypacker’s new novel, has the rare quality of isolating its subject to the point of making the story a living portal for its readers. The story’s motion is rendered in precise parallels and dynamic echoes. Apples fall passively from a tree. A toy soldier is hurled as far as it can be thrown. A boy’s father and grandfather passively remain where they have fallen. A boy, Peter, and his fox, Pax, separated by a moment of falsity, struggle independently to return to where they belong, to be reunited. Porch doors are left open.

Pax, Sara Pennypacker’s new novel, has the rare quality of isolating its subject to the point of making the story a living portal for its readers. The story’s motion is rendered in precise parallels and dynamic echoes. Apples fall passively from a tree. A toy soldier is hurled as far as it can be thrown. A boy’s father and grandfather passively remain where they have fallen. A boy, Peter, and his fox, Pax, separated by a moment of falsity, struggle independently to return to where they belong, to be reunited. Porch doors are left open.

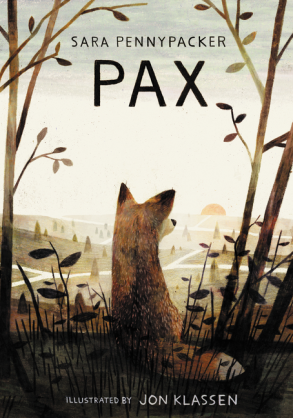

A book that successfully explores, describes, and embodies the operation of truthfulness provides a gauntlet of irony for anyone trying to describe it. Labels must necessarily miss the mark, for they are static and the process of truthfulness is dynamic. For example to say that Sara Pennypacker’s new novel, Pax (HarperCollins/Balzer + Bray, Feb. 2016), is an exceptionally powerful story is as easy and true as pinning down the reasons for that power are elusive and variable.

Pax deals with the topic of war, yet Pax, above all else, is not about war so much as it is about truth and self-knowledge. At every point it affirms that truth and self-knowledge are moving targets and that staying in their center is a matter of active personal responsibility and effort. Passivity and stasis lead to a growing distance from true selfhood and, therefore to self-deception and falsehood. In the context of the book war is an engine of creating distance from truth and self-knowledge. It ravages the physical world and violently reshapes the interior worlds of everyone in its path.

Peter’s father, a career military officer in a family of career military officers, is heading off to join the war. Peter is pressured by his father to leave his fox Pax behind on the day when Peter is being relocated to his grandfather’s house, hundreds of miles away. The scene is viscerally captured through Pax’s experience. That night Peter realizes that he cannot stay at his grandfather’s, that he is not where he needs to be, which is reunited with Pax.

The story unfolds as a dual narrative, alternating between Peter and Pax. Peter’s journey leads him into connecting with Vola, a veteran who has lost a leg, and lives in isolation searching to restore her own true self, and to atone for her variance from it. Peter needs to be with Vola at that moment, but he got to that place where he needed to be by trying to get to Pax. In a parallel sense Pax ends up in the wild, where he needs to be, as a result of an act of falsity. Their parallel journeys to be reunited come together at the exact point at which the story began except that everything has been transformed.

In declaring that even a great distance from truth and self-knowledge can be overcome with sufficient will and effort, and in making personal responsibility a cornerstone for that effort, Pax challenges the reader strongly and directly. Its clean lines and clear motion heightens that challenge. The narrator of Notes from the Underground noted that “and what can we say of war, they fought before, they’re fighting now, and they’ll fight again.” That is certainly true. Pax asks its readers whether they are willing to let that be their truth. This book, which is so much about getting to where you need to be, deserves all the publicity and award consideration it is certain to get because where it needs to be is in readers’ hands.

Note: due to a spam attack, the comments section of this blog has been temporarily disabled. We hope to have it up and running soon!