It’s astonishing how accustomed we’ve all become to a certain tone in middle-grade books, a voice or mood that’s become so familiar it takes something radically different to remind us of the fact that there are many, many different ways of telling stories. A nation’s political situation, social context, attitudes, trends, or popular culture can’t help but influence writers, and writing trends and storytelling habits emerge and change along with them. Writing styles and trends wax and wane, but even gone, they leave their mark on subsequent generations of writers.

It’s astonishing how accustomed we’ve all become to a certain tone in middle-grade books, a voice or mood that’s become so familiar it takes something radically different to remind us of the fact that there are many, many different ways of telling stories. A nation’s political situation, social context, attitudes, trends, or popular culture can’t help but influence writers, and writing trends and storytelling habits emerge and change along with them. Writing styles and trends wax and wane, but even gone, they leave their mark on subsequent generations of writers.

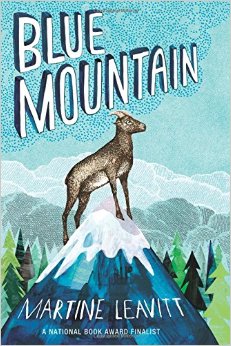

It’s so rare to feel that exciting kick in the gut that signals something fresh and deep and true, done differently. I had that feeling immediately when I started reading Martine Leavitt’s Blue Mountain. I’m not sure if Leavitt’s Canadian roots account for this book’s uniqueness, but sometimes it takes a book from another culture to spur this kind of reading awakening. Styles of narration, types of stories, even favorite themes, can vary wildly between countries, giving us stories that stand apart from our habitual daily fare, as delicious as it may be. Reading Blue Mountain is like drinking a glass of clear cold water after having chugged sodas for a week.

So much about this book feels like a return to classic storytelling. It is old-fashioned (and by this I think I mainly mean that the narrative is patient, deliberate, without being staid), full of starkness and beauty, joy and sorrow, danger and gentle calm. Readers who loved Where the Red Fern Grows and The Yearling and especially The Call of the Wild should find a new timeless tale to love here. Blue Mountain is the story of Tuk, a bighorn sheep whose world is threatened by natural predators and human encroachment. Young Tuk is large, and his approving herdmates assume that he will grow up a leader. Further signaling his specialness is Tuk’s ability to see, now and again, a mystical blue mountain in the distance that is the stuff of legend among his kind — a safe homeland for bighorn sheep beyond the reach of dangers. As humans build higher and higher up the mountains, there’s a chain reaction; animal predators are emboldened and there are fewer resources for the hungry bighorns. When Tuk leads a group of his fellow sheep away from their grounds to find the blue mountain, he encounters challenges that test his strength, intelligence, and wits.

The pace of the book has a rhythm like nature itself: it unfolds with stretches of peace and moments of high intensity. It isn’t afraid to be sober. It doesn’t shy away from the sudden brutalities of the natural world, but deals with them gracefully.

Blue Mountain is an animal unto itself. Like Tuk, Blue Mountain forges its own path, unconcerned with the exigencies of sheep beyond its herd. It isn’t for every young reader, but will resonate and stay with those who love nature and linger in dreams of wilderness, destiny, adventure, and myth.

Thank you, Elizabeth. That will be my next book. It sounds perfect.

Thank you! We bought it but haven’t yet given it a close look. Whom do you think is the core audience for it?

Carol, I’d recommend readers 9-13 who love animals and adventure, the ones to whom you’d recommend Where the Red Fern Grows and The Yearling and The Call of the Wild.

Beautifully written, Elizabeth. I can’t wait to read this now.