The model of exclusive proprietary content, which has become the centerpiece of competition in the video streaming arena, would be the death of that fraught and wonderful sphere which is home to us all: traditional publishing. Cloverfield Paradox only on Netflix. Transparent only on Amazon. Handmaid’s Tale only on Hulu. Translate that to books. The new Barbara Kingsolver, only on Amazon. The new Sarah J. Maas only on Amazon. The death knell of traditional publishing and independent bookselling, available everywhere.

Amazon’s publishing ventures have stood in contrast to those of professional publishing houses whose wares are open to all retailers. These Amazon proprietary publishing efforts feed their own exclusionary retail channel, building up a vertical monopoly with the potential to lure increasingly strong proprietary content into its enclosed production and distribution system. Other related efforts include leveraging the power of its own bestseller lists and that of vertical acquisitions such as Audible, ABE, and Goodreads, along with their near monopoly on ebooks. These efforts, like those of the Swedish army sappers during the siege of Jasna Gora, have had the effect of weakening and undermining the integrity and foundations of proprietary publishing’s open access to all retail channels.

Amazon’s publishing ventures have stood in contrast to those of professional publishing houses whose wares are open to all retailers. These Amazon proprietary publishing efforts feed their own exclusionary retail channel, building up a vertical monopoly with the potential to lure increasingly strong proprietary content into its enclosed production and distribution system. Other related efforts include leveraging the power of its own bestseller lists and that of vertical acquisitions such as Audible, ABE, and Goodreads, along with their near monopoly on ebooks. These efforts, like those of the Swedish army sappers during the siege of Jasna Gora, have had the effect of weakening and undermining the integrity and foundations of proprietary publishing’s open access to all retail channels.

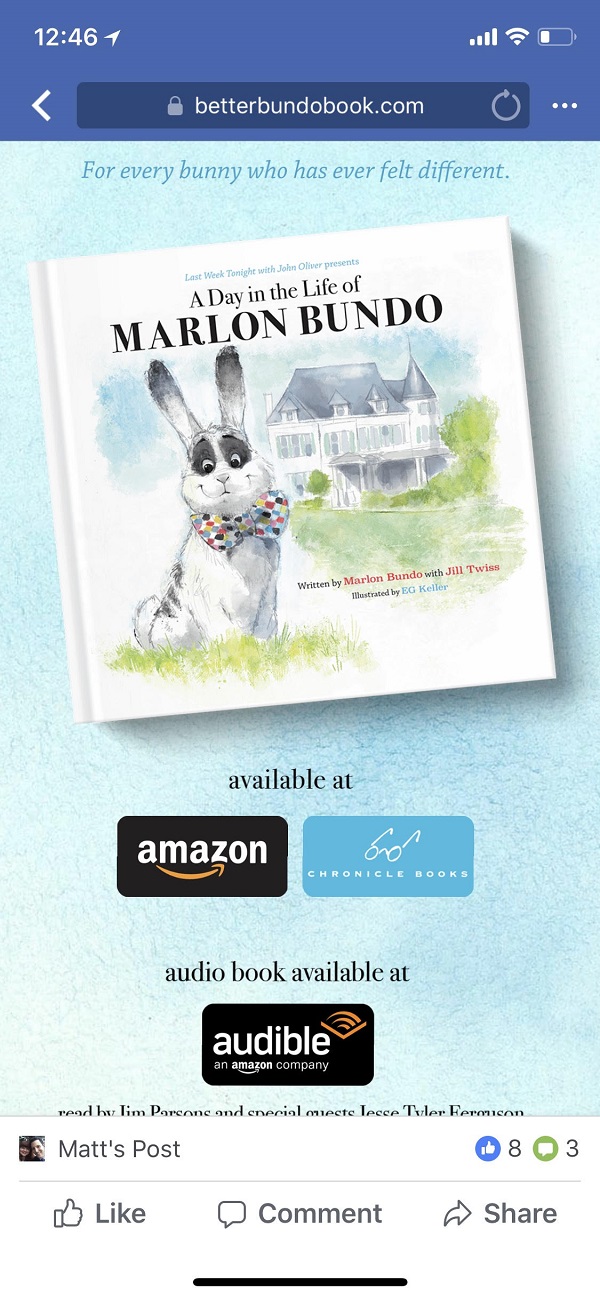

A strong new step toward damaging Amazon’s remaining competitors in the retail book trade, and establishing the model of exclusive book content, occurred Sunday night with the exclusive window for ordering afforded to Amazon upon the crash release of A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo on the Last Week Tonight with John Oliver show. This three-day window was enabled by providing them with exclusive advance product information including the fact of the book’s existence, all product details, and the finished ebook for both sale and use as a look-inside driver for print book sales. The product information was not provided to regular industry Onix feeds until after the release, leaving Ingram, Baker and Taylor, and everyone downstream from their data completely flat footed both technically and promotionally. This created a sales exclusive for Amazon during the critical period surrounding the high profile release and reveal. The complete absence of any other retail channel can be seen in this New York Times article which refers to no standard of measure other than the Amazon and Audible bestseller lists, and no other means of distribution either. The article could well have been written in a post independent bookselling, and even a post-New York Times bestseller list world.

A strong new step toward damaging Amazon’s remaining competitors in the retail book trade, and establishing the model of exclusive book content, occurred Sunday night with the exclusive window for ordering afforded to Amazon upon the crash release of A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo on the Last Week Tonight with John Oliver show. This three-day window was enabled by providing them with exclusive advance product information including the fact of the book’s existence, all product details, and the finished ebook for both sale and use as a look-inside driver for print book sales. The product information was not provided to regular industry Onix feeds until after the release, leaving Ingram, Baker and Taylor, and everyone downstream from their data completely flat footed both technically and promotionally. This created a sales exclusive for Amazon during the critical period surrounding the high profile release and reveal. The complete absence of any other retail channel can be seen in this New York Times article which refers to no standard of measure other than the Amazon and Audible bestseller lists, and no other means of distribution either. The article could well have been written in a post independent bookselling, and even a post-New York Times bestseller list world.

The influence of the video streaming exclusivity model is evident in HBO’s role in the release. There were many complications here regarding their desire for a full embargo. Chronicle was in a sticky position. What we do in difficult times counts the most, however, and it falls on the publisher to say “we don’t do that in publishing, we can include all our customers and still achieve the desired embargo.” That position would have had the added benefit of being true.

The health of the independent and chain retail channels is vital to the continued survival of the publishing industry. One can see this in Chronicle executive editorial director Sarah Malarkey’s statement on the value of inclusiveness. “I’m so proud to have published this book. It is completely aligned with our core values and our support of inclusiveness and democracy.” One feels, however, that inclusiveness pertains to a publisher’s own retail bookselling customers, and that harming Independent Booksellers to facilitate an outside demand for exclusion does not meet the core principle of inclusion.

The guiding principle of exclusivity is taken from the medieval thinker William of Ockham’s observation that “Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity.” To understand this sticky issue William himself was kind enough to answer a few questions here.

Kenny: Thank you for taking the time, William. Before I start, I have to ask one personal question. I know the term Occam’s razor, for which you are famous, did not come into play until many years after your death. Do you like the term?

Kenny: Thank you for taking the time, William. Before I start, I have to ask one personal question. I know the term Occam’s razor, for which you are famous, did not come into play until many years after your death. Do you like the term?

William: Am I not clean shaven?

Kenny: Good point. Turning to the matter at hand, does your principle that “Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity” apply to the publishing industry?

William: Yes it does, but it also depends on providing the definition of necessity. Take politics. Autocracy is the simplest form, of course, but that is a solution to a very specific question and not the one you may have asked. First you must apply your values to establish the simplest principle. That principle, once established, is then applied to determine the nature of things. If your goal is life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, autocracy hardly answers. The entity in this case is your principle, not the number of retail channels. If you value a dynamic, curated but independent intellectual marketplace, the answer lies in publishers supporting all their customers, particularly those who share their principles, not just those seeking the monopolization of power and resources. The drive to singularity, efficiency, and simplicity is anathema to your principles and therefore to your complex industry.

Kenny: Interesting! You do keep up with current events, William. I’m impressed.

William: My time is, let us say, my own at this point.

Kenny: I take your point, though.

William: Yes, the humanists well understood that for the complexity of human artistry and expression to flourish independence was a core necessity. There is such a thing as healthy complexity. Adopting the justifications for quick gain on the grounds of a false necessity is short-sighted indeed. Independent booksellers are well able to handle and participate in embargoes and specialized releases. Publishing houses should not fall into the trap of allowing their proprietary assets to be fuel in a blaze of exclusivity which will bring down their own houses in the conflagration. Core values have no boundaries.

This is a perfect analysis of the problem called Marlon Bundo. The increasingly familiar irony is that something intended to support fundamental democratic principles of representation and inclusivity in our country’s government, was in itself, a vote for monopsony. A lose for free expression and culture. Great piece Kenny!

‘Amazon’s publishing ventures have stood in contrast to those of professional publishing houses whose wares are open to all retailers.’ Certainly those wares are open to all retailers, but everyone does not get published by professional houses. Amazon explored a new concept, everyone can get published, and it worked for them. I have watched as the Indies have missed every boat since the digital age. Remember when Jeff Bezos was on his knees packing books in his garage with his wife the ABA had over 4,000 stores and a trade show with millions, they had the resources to make a work class Ecommerce site but did not. They had the resources to set the standard for EBooks but they did not. They could have very easily partnered with a printer for those authors who self-publish but did not. Yes the have their own exclusive retail channel, that’s because they invested the time and the money to do just like EBooks. I see Amazon promoting more voices, opinions, ideas and new authors through many methods, including Kindle. Amazon has increased the democratization of book sales well beyond any point in human history. Amazon is being attacked for investing billions of dollars in a platform that consumers enjoy. There’s nothing stopping the Indies from setting up their own platforms to distribute books except their own stinginess and snootiness.

OliverOptic

As usual, you have hit the nail squarely on the head, Kenny.

Excellent and important piece.