Kenny Brechner of DDG Booksellers in Farmington, Maine, is guest blogging today. He is responding to a question posted on the NECBA listserv about censorship in the bookstore, specifically surrounding Tintin titles. I’m grateful to Kenny for sharing this with, as he dissects the issue clearly and cogently.

Bookstores are sometimes asked by customers to remove titles that the customer finds offensive.  The classic graphic novel series by Herge, Tintin, garnered this unhappy attention recently at a friend’s bookstore. It is an interesting issue. Bookstores are not censors in the strict sense of the word, however to remove a book by virtue of an objection is certainly in that neighborhood. How to address this thorny situation?

The classic graphic novel series by Herge, Tintin, garnered this unhappy attention recently at a friend’s bookstore. It is an interesting issue. Bookstores are not censors in the strict sense of the word, however to remove a book by virtue of an objection is certainly in that neighborhood. How to address this thorny situation?

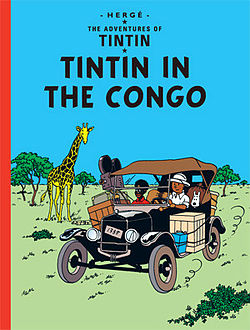

Sam Gamgee was of course mistaken in the “notion of his that the kindness of dear Mr. Frodo was of such a high degree that it must imply a fair measure of blindness.” I believe it to be of the first importance to be kind, but not blind to the embedded biases and prejudices we find in beloved literary works such as Tintin. The integrity of the present is dependent on the integrity of the past. We need to understand the complex dual historical continuum of enduring artistry and base cultural biases which are almost always intertwined. Herge’s Tintin in the Congo, which is not available in an edition for children in the United States at present, has long been cited as an example of unfiltered imperial colonial prejudices. For many of us it is certainly uncomfortable to see these elements mixed in with the familiar voice of a Tintin tale. The impulse to expunge rather than understand reinforces the very blindness it decries however. Recognizing the fallibility and bias of beloved works of literature is a matter for understanding not for removal, the impulse for which is quite as destructive as any embedded historical bias. Reading Tintin in the Congo offers us  an opportunity to broaden our understanding and see our own world with clearer eyes.

an opportunity to broaden our understanding and see our own world with clearer eyes.

Herge’s Tintin in general contains many historical biases from his present. Are any of us free from biases that will be painfully apparent to the eyes of future generations? The Marx brothers were progressive and socially conscience. The inclusion of African-American actors and musicians in A Day at the Races was a progressive choice. Is it nonetheless rife with stereotypes that are painful to behold? Of course. Does that mean that children shouldn’t watch it or that the movie should be erased? Of course not. The fallibility inherent in the human condition is something to share and discuss with children, not shield them from, even as the enjoyment of classic works of children’s literature is something to share across generations. And that, my friends, is the discussion that needs to be had with our censorship-minded customers.

We have several of the Tintin books on our bookshelf at home. They were bought in England in the early 80s from when my husband was a boy living there. They hold a treasured spot, not only because of the memories associated with his time there, but also because they are fun and charming stories. With the popularity of the movie in 2011, I bought several to include in my Middle and Upper School library. I was amused to discover that all of the whiskey bottles (usually so predominate in the Captain’s hand) have been carefully removed from the reprinted editions. Some of the illustrations are hilariously odd now, especially as it’s clear he was meant to be holding something and is apparently not.

Agh! I hate that! We learn from the past, not from whitewashing the past.

I agree that we should not erase racist images from the past, because it is important to remember the context of history. I think that is an essential truth. Though, I would never, as a woman of color, share this with my young child. I think images speak volumes and it would be a more mature conversation to have with a teenager, perhaps, some adults may not even be able to comprehend the enormous and complicated history of images as they relate to Africans, African-Americans, or slavery. I would probably not shelve these editions of Tin Tin in the Children’s dept at a bookstore, either. And I see the value in them, only anthropologically speaking.

The truth is, there are scarce children’s stories published for or by African-Americans, so to defend displaying Tin Tin in a bookstore, in a conversation about censorship, seems like it speaks directly to the lack of diversity in the bookselling and publishing industries.

The broader questions, of whether to “censor” when you have an offended customer, is a valid conversation to have, though to start out with defending a “nostalgic” children’s series that features incredibly painful and racist images of Black people seems bleak, as a Black reader and industry professional, myself.

Thanks for sharing.

Seems to me it makes a HUGE difference whether the books are picture books or almost completely text. Humans are SO visual, and young humans are so vulnerable to external influences on their self concept. We are hungry for picture books like Snowy Day, I Had a Favorite Dress, and Corduroy, where the kids are kids who happen to have darker coloring. We carry many of the biographical picture books that depict the struggle against racial bias, but I don’t like inflicting those on preschoolers, who have no context.

As booksellers, we tend to be hypersensitive to customer feedback, whether about the condition of the carpet or the content of the books. Over the years I have jumped to respond to a customer objection about this book or that, but have always regretted it in the long run. Thank you for running this piece, which helps give us all traction when the going gets slippery.

For a long time, there were two books with two copies on my shelves. One was the original that my husband grew up with, the other was the modern version. I’d read both with my young children and discuss the changes to the illustrations. The cigarette was removed from one. I’m afraid the title is escaping me, but it was about a boy walking with his father. I’d explain why it was included and later cut. The text remained the same in both books. This was a great lesson in how times and ideals change. Unfortunately, the older versions, both paperbacks, have not survived my children.

Well, I’d like to know what his friend whose bookstore it was actually did–and said–to the customer in question. Everyone has prejudices of some sort. Do booksellers have a nice polite reply in general to what amounts to censorship? If you start pulling out all the books (old and new) someone objects to you wouldn’t have much left to sell.